Abbas Kiarostami’s Humanist Legacy Lives on in Universal Language

Spoilers follow for the film Universal Language, released in theaters late last year for an Oscar-qualifying run and expanded to additional markets on February 14, 2025.

A core aspect of Iranian cinematic tradition is a sense of curiosity — a tendency to consider both sides of a story, and both the real and the surreal. Part of this phenomena is fed by the public/private split of Iranian life after the 1979 revolution, a division of inner and outer selves through which what people outwardly say and do doesn’t always align with what they secretly yearn for or desire. Abbas Kiarostami wasn’t the first Iranian director to explore these binaries, often by using moviemaking itself as a narrative device, showing us how we’re always acting a role for both the people we know and don’t. But his legacy has sprawled further than any other, inspiring filmmakers to embrace a kind of humanism where every character — immigrants and criminals and kids, the financially struggling and beleaguered bureaucrats and young people in forbidden love — has interior motivations and acute vulnerability.

You see that legacy in films like 1995’s The White Balloon, which Kiarostami wrote for his former assistant Jafar Panahi to direct. (Panahi would become a regime-challenging cinematic titan himself.) It’s in the works of younger Iranian directors who merged Kiarostami’s implicit class criticisms with portraits of diaspora communities, like Ramin Bahrani’s Man Push Cart and Chop Shop. And it permeates filmmaker Matthew Rankin’s Universal Language, whose bittersweet ending pokes at the connections between who we are and where we’re from, and imagines where we go when the two feel lost to each other.

On one level, Universal Language’s title refers to Farsi, spoken by nearly everyone in the film’s absurdist version of Winnipeg — the city’s Iranian citizens, visiting tourists, Rankin’s own character (also named Matthew), and even the flocks of turkeys that roam the snowy streets. (The film is co-written by Farsi speakers Pirouz Nemati and Ila Firouzabadi.) On another level, the “universality” here is of course the human condition, with all the textures, fissures, chasms, and warmth that Kiarostami advocated for over the course of his career.

Set in a snowy, whimsical Winnipeg in which Iranian vendors push samovar carts, offer up bowls of khoresht stews, and lovingly tend to crocuses amid bland concrete partitions and utilitarian parking garages, Universal Language divides itself into various timelines that ultimately converge in the film’s back half. Before then, what unites the storylines is how matter-of-factly they’re rendered — there’s no explanation for why Winnipeg now resembles Tehran; it just does — and how influenced they feel by various Kiarostami joints. First up is a storyline involving elementary-school children at a French-language school whose teacher, the short-tempered Mr. Bilodeau (Mani Soleymanlou), is like an Iranian version of Paul Giamatti in The Holdovers. Disgusted by his students’ lofty career goals and how poor their grasp of the language is — Soleymanlou yelling “You don’t have the decency to misbehave in French?” is one of the film’s funniest moments — he threatens them all with expulsion after young Omid (Sobhan Javadi) admits he’s once again lost his much-needed glasses, and therefore can’t participate in class.

While nearly everyone else rejoices about being let out early, aspiring diplomat Negin (Rojina Esmaeili, a spitfire with a fantastic frown) takes it upon herself to help Omid. Children coming together to return, retrieve, or replace something lost is a cornerstone of Iranian cinema: Kiarostami’s Where Is the Friend’s House?, the first installment of his Koker trilogy, is about a boy going on an arduous quest to return his friend’s notebook so the other child doesn’t get in trouble for not doing his classwork. A decade later, Kiarostami’s peer, Majid Majidi, would break through internationally with Children of Heaven, in which a boy loses his younger sister’s shoes, and plans with their financially struggling family how to get another pair. And in Kiarostami and Panahi’s The White Balloon, a brother-and-sister duo lose the money they were meant to spend on a goldfish for their family’s Iranian New Year celebration, and try to recover it. In Universal Language, all Negin knows is that Omid was “obstructed by a turkey” in a parking garage and his glasses fell off and disappeared, but she’s undaunted, especially when she finds a 500-riel note frozen in the icy ground on her way home. (In the film, Winnipeg names its money after Métis resistance leader and “father of Manitoba” Louis Riel, which sounds quite a bit like the Iranian currency rial.) All Negin needs to do is hack or melt her way through the ice to the cash, which she can give to Omid for new spectacles — a task that becomes harder when an adult, Winnipeg tour guide Massoud (Pirouz Nemati), also spots the money and seems like he’s going to take it for himself.

While Negin and her older sister Nazgol (Saba Vahedyousefi) race around trying to find a way through the ice before Massoud does, Universal Language starts following a man who feels comparatively aimless. Matthew (Rankin) has spent years working an unfulfilling government job in Montreal, and his return to Winnipeg for his mother’s birthday takes on the quality of a fated sojourn. He can’t quite explain why he spent so much time away, but he easily falls back into his childhood home’s Iranian language, customs, and habits. (Think of how the filmmakers in Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees and The Wind Will Carry Us relate to the people they meet while traveling in rural areas of Iran; they sometimes don’t understand the village dialect or know the town gossip, but there’s a baseline sense of compassion and companionability.)

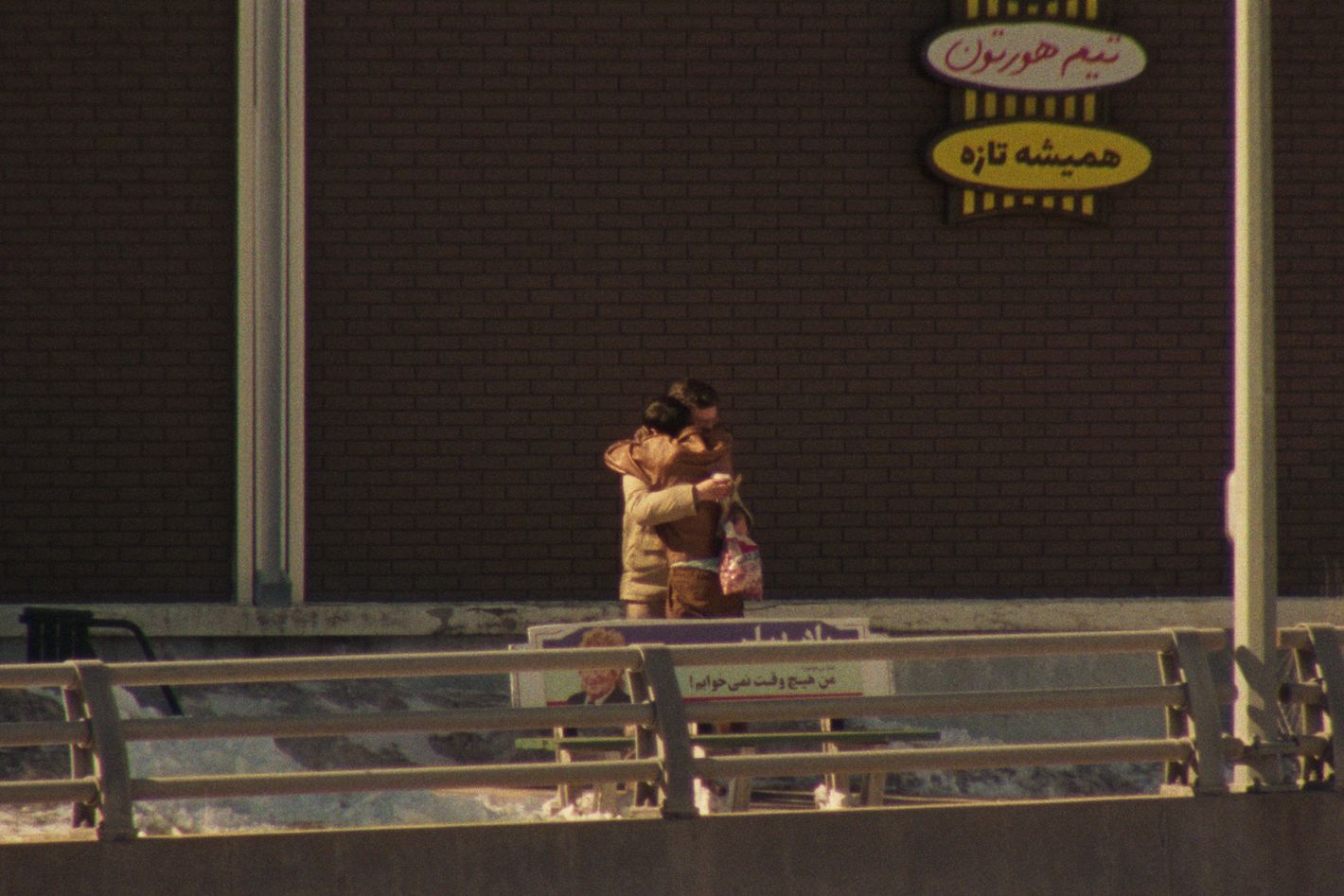

As the wandering Matthew, Rankin lets contrasting depictions of tentative homecoming and wondrous discovery play out on his face. While walking through places forgotten and familiar, he revisits the home where he grew up (in which a welcoming Iranian family now lives), his father’s grave (situated in a little triangle of land between freeways, in a symbolic depiction of coming and going), and a Tim Hortons (where instead of coffee, everyone drinks tea with a sugar cube firmly grasped between their teeth, the Iranian way). He’s a traveler through other people’s lives, not unlike the cab driver of Kiarostomi’s Taste of Cherry, who learns a bit about each of his passengers before asking if they’ll bury him after he dies by suicide. Matthew’s end may not be that explicitly planned, but a death of sorts does await him. That becomes clear when Matthew finally meets Massoud, who answered Matthew’s mother’s phone and directed him to the apartment where they live together. With that encounter, Universal Language transitions into its final homage: to Kiarostami’s 1990 masterpiece, Close-Up.

Close-Up, about the real-life relationship between Iranian cinephile Hossain Sabzian and director Mohsen Makhmalbaf (who Sabzian impersonated for a period of time in the late 1980s) was the zenith of Kiarostami’s obsession with prodding at filmmaking’s tradition of positioning directors and writers as active crafters of myth and audiences as passive absorbers. The film collapses the boundaries between these different groups, and with its cinema verite style, acknowledged Kiarostami’s own role in recreating this story; Kiarostami’s crew, Sabzian, Makhmalbaf, the family who Sabzian conned, the judge overseeing Sabzian’s trial, and numerous other people involved in the real case play themselves. The whole thing is an empathetic mindfuck of cinematic form and function, and an insightful portrait of how we center ourselves in our own narratives to feel special, known, and wanted. (Makhmalbaf would use the same director-playing-themselves device in his 1996 film A Moment of Innocence, in which he acts opposite the actual policeman he stabbed at a protest in his youth.)

Universal Language takes that model and uses it for its own ending, in which various story threads come together: Nazgol finds Omid’s glasses wrapped around a turkey’s foot and wrestles the bird for them; Massoud steals the 500 riels from the sisters and takes the ice block in which the cash is still trapped home to thaw; the sisters learn that Massoud is actually Omid’s father when Omid and his mother, overjoyed at the return of the boy’s glasses, invite them over to eat cake and celebrate Matthew’s mother’s birthday; and Massoud is shamed by how he tricked the girls by promising to keep the frozen cash safe.

Matthew, who met the sisters and Massoud separately before they all unite in Massoud’s apartment, understands how the cash came between the two parties. But he can’t view Massoud as a villain when he learns the degree to which the man and his family have been caring for Matthew’s ill mother, who because of her dementia thinks that Massoud (who used to shovel her sidewalks) is Matthew, the son who left her and Winnipeg behind. Where Massoud was disgraced by how he conned the young, Matthew is chastened for how he forgot the old; each of them is a betrayer. Matthew’s first steps into his mother’s bedroom are tentative, his body pressed against the wall and in flickering shadow. The camera doesn’t move as Matthew’s face, with its expression of regret, is reflected in a large mirror on his mother’s mantlepiece. But when Omid enters the room and excitedly greets the woman he’s come to consider his grandmother, we get that same shot, and now Matthew’s face is reflected in a smaller mirror than Omid’s. His role is diminished in her life, and although photographs from his childhood sit on that mantle, too, his mother no longer thinks they’re photos of him. She thinks they’re photos of Massoud, whom she knows as Matthew. Massoud had explained the swap to Matthew when they first met — that Matthew’s mother told Massoud “the story of the day I was born, my first steps, my first words,” and they became Massoud’s own memories, too. Massoud inhabits two lives, while Matthew doesn’t realize he’s been erased from his own.

The transfer is so porous that when Matthew leaves his mother’s room and looks at Massoud, Negin, and Nazgol still bickering about the found money, he’s no longer himself: Just like Winnipeg transformed into Tehran, so too does Matthew become Massoud, with Nemati now playing Matthew. As with Matthew’s mother’s mirrors, again Rankin uses mimicked framing to replace his character. When Massoud and the sisters, center-aligned, stare directly into the camera, they destroy the fourth wall between subject and viewer (as Kiarostami did by so often inserting himself into his own films) and set us up to see Matthew-as-Massoud staring back at them. In return, center-aligned Matthew-as-Massoud also stares directly into the camera, and prepares us to see Massoud-as-Matthew (with Rankin now playing Massoud) in the next shot. No one but Matthew-as-Massoud clocks anything wrong here. It calls to mind how in Close-Up, Sabzian mimicked Makhmalbaf for a while without anyone catching on. But Universal Language doesn’t treat Massoud and Matthew’s body swap as an action to be punished, like Sabzian initially was. Instead, it uses their interchange to wonder at what exactly makes us who we are.

What qualities, signifiers, and characteristics are most essential to making us us — is it our families, our names, our faces, our voices, our jobs, our choices? Is it how we present ourselves to strangers, or how loyal we are to those we love, or how far we’ll go to right a wrong? Outside of a general unhappiness with his job in Montreal, we know very little about who Matthew is, especially in the context of his relationship with his mother. What Universal Language seems to suggest is less that Massoud stole Matthew’s selfhood, though, and more that Matthew let that person slip away. Perhaps he cared more about his career than himself. Perhaps he got caught up in bureaucracy. Perhaps it was easier to avoid home after his father’s death. Whatever his reasons, Universal Language maintains its fizzy-as-doogh effervescence, and refuses to give into cynicism or judgment about Matthew-as-Massoud’s path forward or curse him to a life without further individual choice; just because he now looks like Massoud doesn’t mean he has to make the same mistakes.

Instead of pocketing the 500-riel note when the ice trapping it finally melts, Matthew-as-Massoud walks back to where it was found, puts it back, and pours water over it so it can freeze again. In this small way, he can turn back the present and return to the past; in this significant way, he can create another opportunity for someone to find this money and change their future with it. Time is malleable, reality is only a function of our choices, and people can create their own second chances — ideas that Universal Language borrows from Kiarostami’s cinematic library of compassion, and then makes its own. When Universal Language begins, an intertitle with a yellow turkey illustration claims the film is “A Presentation of the Winnipeg Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young People”; it’s a cutesy Easter egg for people who know that Kiarostami’s early short films and documentaries about kids were affiliated with Tehran’s Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, and that the Kanoon organization was represented by a green goose logo. But you don’t need prior knowledge of the next on-screen text to understand its intent: “In the name of Friendship” is an immediately clear mission statement. That too is lifted from how Kanoon prefaced its films with the same phrase in Farsi, but its use here feels like an admission, not just mimicry. What could be more revealing, fragile, and intimate — in any dialect — than the loneliness that pushes someone’s attempt to make a friend? Through a resurrection of Kiarostami’s openheartedness as cinematic practice, Universal Language crafts its own identity.

Related

Latest News

For Sale! 2016 Sea Ray 350 Sundancer – $180,000

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

A Comprehensive Guide to the White Isle

Ibiza: The Vibrant Heart of the Balearics in 2024 Ibiza, the sun-kissed...

Roschman Sells Boathouse Marine Center to BlueWater for $16 Million

© Copyright – autocontently.com

Man United seals spectacular comeback to beat Lyon 5-4 and advance to Europa League semifinals

Manchester United’s season isn’t done yet. On a night of high drama...

NCAA panel gives final OK to rule designed to discourage football players from faking injuries

The NCAA Playing Rules Oversight Panel gave final approval to a rule...