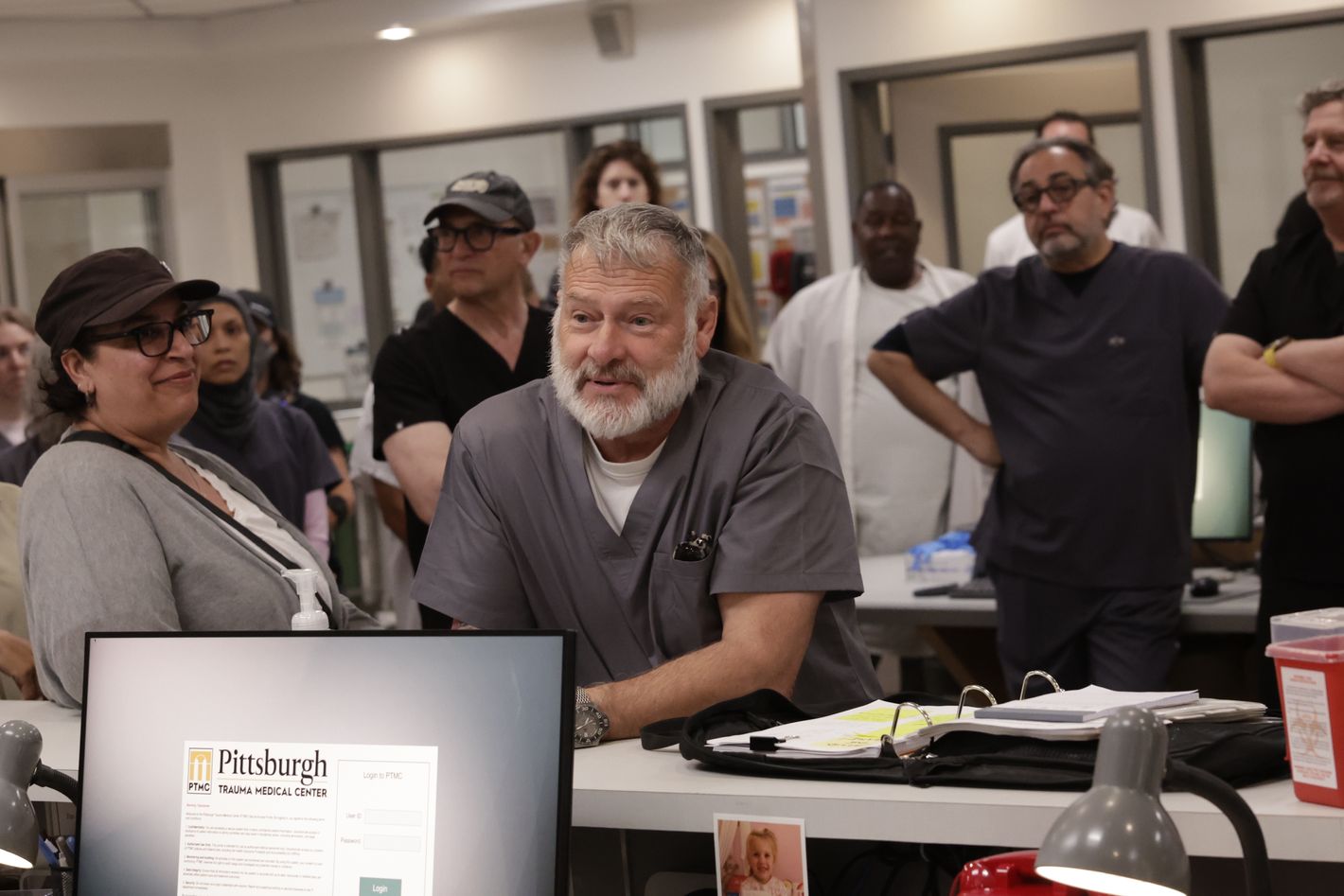

The finale of The Pitt feels like an exhale. Up to this point, Noah Wyle’s Dr. Michael “Robby” Robinavitch has managed a mass-shooting event, a patient sucker punching his charge nurse, a brooding teenager whose mother worries he might cause harm, a resident’s near arrest for tampering with her ankle monitor, and his own unprocessed pandemic PTSD. There’s also a host of brand-new, inexperienced medical students; a staffing shortage; and the hospital administrator breathing down Dr. Robby’s neck. In the final hour of the shift, The Pitt is still full of tumult — the patient with a fork through her nose, for one — but its pace has slowed significantly. The doctors and nurses who have been sprinting through the ER for the past 15 hours finally have a moment to breathe.

Co-creator and showrunner R. Scott Gemmill describes the goal for season one as “Let’s put on a show and figure it out as we go.” The Pitt is unlike most streaming series in that way — many have fully finished scripts before filming begins, but the Max show operates with a system closer to a network-style production process with scripts written and reworked during production and episodes shot roughly chronologically. This model allows Gemmill and the other writers to adjust and react to discoveries in casting and filming. “I like to have an idea of where we’re going but hang on to it very lightly,” he says. “We have the option to change course, to go with the most interesting or what feels most realistic or authentic.”

The Pitt is not a partisan exercise, but it is unflinching in its portrayal of how public policy and the broader cultural conversation affect medical practitioners. Gemmill is frank about what he hopes viewers will take away from the series: “It’s not about trying to sway anyone with a personal agenda. It’s about showing what society is faced with. People forget that the ER is the safety net for our society, and it becomes more so every year.”

Your initial pitch for the series was a 12-episode season and then Max requested you push it to 15. How did you adjust the season arc to fill that extra time?

Streaming numbers are somewhat arbitrary, and the typical shift at a hospital is 12 hours, so 12 episodes makes perfect sense. But Max wanted 15, and the truth is just because you’re working a 12-hour shift doesn’t mean you’re working 12 hours. You come in early, and the amount of charting doctors and nurses have to do — sometimes you just stay there rather than go home. From the get-go, one of the arenas we wanted to explore was the ongoing problems with mass shootings. We didn’t have to come up with an artifice to extend it.

How far were you into developing a 12-episode season before you had to go back and rework it for the 15-episode structure?

At the beginning, 12 or 15 is sort of arbitrary. The end is going to be the end. The bigger challenge was, Where do we put the mass casualty? We could’ve ended at the end of episode 12 — there were days when we kind of wished we had, when we were getting tired. Where was Robby’s meltdown going to happen? Do we put it in the middle of the mass casualty, or is it toward the end? And then after the mass casualty, how many episodes do you do? You don’t want to end on that. You don’t want to have this great three episodes of chaos and then an anticlimactic ending. That was more of the challenge than figuring out 15 episodes. And I know for a fact that if we wanted to do 18 episodes, they would embrace that. But it’s a lot to ask of our crew. Fifteen episodes of our show is like 24 episodes of a regular season of television.

How did you think about what this last episode should be? It’s less climactic than what we’ve come to expect from a streaming series.

We didn’t want to do a big cliffhanger. We didn’t know if we were going to be back, and if there wasn’t a second season, I would never want to leave an audience in the lurch. We could’ve walked away from this feeling satisfied. We had an idea of how we wanted it to end: The scene in the park, the scene on the roof, the scene with Abbot in front of the hospital with Robby — those were all written and shot in September.

Some of the very big emotional scenes we’ve seen over the last few episodes, like Langdon getting kicked out, Dana talking about working at the hospital after she was punched, Collins sitting in the back of the ambulance — those were all audition scenes. We wanted to get those characters to those spots. When you’re casting actors who are not going to get there for 12 episodes, you have to have those scenes tried out. We had to write to them. One of the big jokes Noah kept giving me a hard time about was up on the roof, Abbott says, “Nice speech. I wish I’d given it.” When we shot that in September, there was no speech written. And Noah kept saying, “I can’t wait to see my speech!” And I was like, “That makes two of us, because I have no idea what that stupid speech is supposed to be.”

I did wonder how much the earlier plotlines were designed before you added the mass casualty, especially for McKay and the troubled teen, David.

That was a story I really wanted to tell: How do you get a child you’re concerned about the treatment he needs when he’s not going to want to go along with it? We knew we wanted to talk about mass shootings. Gun violence is such a horrific part of this society, and the statistics are so horrific for young people. That was something we wanted to address — and the aftermath, not just for the victims and the survivors but also the people treating them. There’s a real problem in society with young men trying to find identities that have changed drastically over the last 40 years. There’s a reason a lot of the people who commit these crimes are young white males of a certain belief system, or frustration, or lack of identity. This seemed to be a perfect combination of stories.

Did you always know the David plotline would end with him not having committed the shooting?

No, we went back and forth a few times. I like to have an idea of where we’re going but hang on to it very lightly so that we have the option to change course, to go with the most interesting or what feels most realistic or authentic. I appreciate having the ability to explore things without commitment until we figure out the best way to tell a story. Deep down, I never wanted this kid to do it, but that might’ve been because I liked the actor, Jackson Kelly, who played the part.

The dilemma between McKay and Robby was fairly grounded in the sense that they were both sort of right, but somebody had to make the decision, and she felt like he wasn’t making it in due process. So she took it upon herself.

It is Robby who flags David to the police though, right?

McKay is the one who’s pushing to flag him, and she first calls the police. That’s why he’s surprised when they show up. It’s why he’s so angry with her.

But it seemed like Robby was blaming her for something he’d done himself. He told the cops to talk to Theresa after the shooting started. His anger in episode 13, when he tells McKay to clean up her mess, felt unfair to me.

Robby initially doesn’t want to involve the police for what he considers a thought crime. Theresa made herself sick to get her son here, so Robby isn’t even sure how stable she is. McKay doesn’t want to be wrong about this and calls the police and tells them about David’s “list,” but it’s nothing the cops can really act on. Now Robby is angrier with McKay because she went behind his back and against his wishes.

Once the shooting starts, Robby points out Theresa to the cop who brings in the first casualties in the ambulance bay. Robby says he’s not sure her son had anything to do with it, but he wants the cop to speak with her just in case. Robby wants to believe David is innocent but also knows somebody’s responsible for this. He would be remiss if he didn’t tell the cop to follow up on David. Robby has been doing this a long time — much longer than McKay — so he considers himself to be a better judge of David’s mental status, but he can’t dismiss David’s involvement outright until they locate the shooter.

It’s not black and white for Robby, and that’s where the uneasiness and anxiety come from. This isn’t a situation he can cure with a little bit of medicine. And, yes, Robby is off his game today. It only gets worse as the day goes on and the stressors accumulate. He’s angry with Langdon, upset with Collins, pissed with McKay, all in addition to Gloria riding him for patient satisfaction, the death of Adamson, the day’s patients … and now a mass-casualty situation — not to mention the death of Leah and his own meltdown. Is he blaming McKay for things that aren’t her fault? Possibly. He’s bouncing back and forth and starting to question himself. This is why we begin to see him snapping at people and he even tells McKay to clean up her mess. On another day, Robby could have handled things better. Not so much today.

That’s what’s great about the writers’ room: Somebody comes up with a great idea, you throw it out there, then it’s like a bunch of jackals trying to get at the freshly downed gazelle.

It sounds like writing was unusually flexible for a streaming series. Were there things you adjusted as you went or as characters got cast?

Absolutely. I tend not to write with actors in mind, but once you cast the actors, you learn what they do well; you learn their cadence, their speech patterns, their comedic timing. That’s the best part of the whole business. What Gerran Howell can do — the stuff with him getting peed on — none of that was initially in the script. Javadi and Mateo, that came out of casting two people who were really cute together. McKay’s ankle bracelet was a last-minute need to say, What can we do to make this character a little more interesting? What can we do to make her more complicated? Katherine LaNasa offering a mint to Gloria — that was something Katherine picked up from real nurses. If you keep your mind open and hold things loosely, you allow for wonderful things you would never have thought of ahead of time.

Adding the ankle bracelet late surprises me! How did you weave that back into the season?

We’d written about ten episodes before we started shooting, and I’d never done that. It meant we had time to go back and make adjustments accordingly. It was probably while I was writing episode two or three that we figured out the ankle bracelet. It just felt like McKay needed something else in that character. It’s easy to drop it in, but then it’s like, How do we get it off her? When does it go off? How is she going to disable it? Does she put her foot in a bucket of bloody water? Little things like that can snowball. That’s what’s great about the writers’ room: Somebody comes up with a great idea, you throw it out there, then it’s like a bunch of jackals trying to get at the freshly downed gazelle.

You’ve decided season two would take place on the Fourth of July, right?

People were like, “Is it the next day?” But no — it can’t be the next day, because everything will have just happened, and everyone will be dealing with the PTSD of that. It’ll be the most somber 15 hours. We wanted to have enough time, and we wanted to have some things happen. If Langdon were to return, for instance, he would’ve needed to do a certain amount of in-treatment rehab.

Do we want to do a night shift? Do we want to do a winter season … ? We’re not quite there. Maybe we get another season or two under our belts before we go back for winter. Eventually we have to go there; we just have to get our blood thickened. And we knew we’d be shooting again in Pittsburgh in September, so we’d want to match September for somewhere between May and October. Summer comes with a lot of medical issues: Fourth of July has a bunch of things, and we’d done a holiday last season, Labor Day. It just fell into place. There’s fireworks; somebody doesn’t do so well at a hot-dog-eating contest; somebody’s sunburned. You can see all the cases wandering in.

Season two will be 15 episodes again?

Yeah, it’s tempting to do more, but it’s very difficult on our crew. I’d rather tell a tight 15 than a floppy 18. And one hour per shift — I think it was a good exercise for us. It really forces you to have a different kind of storytelling.

How does it change the storytelling?

You can’t jump ahead. There are some episodes of television that take place over days or weeks, so you can jump a lot of story and backfill things. But if I have Robby in North One and next scene I want him in South 22, I gotta figure out how to get him there. You can’t compress stories for the sake of storytelling. But it was also for dealing with personalities — we have people meeting each other for the first time. How much can you get to know someone in 12 hours? Depending on your personality, you’re not going to spill your guts right away. It was challenging to get the audience to know these characters and make it natural without doing a bunch of exposition.

I realized partway through the season that I’d become so fond of these characters and then I worried that because of rotations, we wouldn’t see some of them again in a second season.

We’ve been grappling with that. Some of them are still med students, so they’ll be here for a little while, and some can make decisions. But some people will have to move on, and that’s counterintuitive to a successful TV show where people start to really like characters. Hopefully that’s a problem we have to deal with two or three seasons from now. For the moment, we’re just dealing with it season by season.

Now that you’ve had this mass casualty, do you think each season needs to have one big shocking event?

I don’t think so. It’d become formulaic, and if you look at the feedback we’d gotten, up until episode 11 there hadn’t been anything substantial of that ilk. That was a really good sign because it showed us that we don’t have to do something catastrophic each season. We may do some things that cause some hiccups within the ER, but I’m not sure we’ll go mass casualty every season, because it would feel false eventually. One of the things we really try to do is be pretty accurate and keep the sensationalism down to a dull roar rather than get the audience to react. We’re pulling the audience in, more than doing a spectacular light show; it’s more intimate, and that’s what they’re responding to.

What has brainstorming for season two looked like?

Before I came into the room for season two, I had four or five pages of stuff to talk about. Safe-haven babies. ICE in the ER. A few diseases. A guy shows up, they call his wife — she’s still his emergency contact, but they’re not together because of his behavior. Then maybe it turns out he has early onset Huntington’s disease and this is what changed his behavior and caused her to leave. There are so many things going on; you just have to open a newspaper. Where do you start? For us, it’s not about finding stories — it’s about deciding which ones not to tell.

Regarding the show’s politics, do you think of The Pitt more in terms of illustrating certain realities of the health-care system or of persuading them?

We talk to experts every week, in some cases multiple times a week, whether they’re experts in PTSD in the workplace, or individuals on the spectrum, or immigration policy, or what’s happening with Medicare. We’re trying to be a voice for the health-care frontline workers, and one of the last questions we always ask someone is “What is the one thing you want people to know that they don’t know about your profession?” It’s shining a light on a situation so everyone realizes how tenuous it can be. There’s already a health-care crisis, but there’s an even bigger one looming.

The measles story line does feel specifically pointed in this era.

One of the differences with doing this show now versus a medical show we’ve done in the past is that we’ve never had to deal with this level of disinformation. There was always misinformation, which is different. It’s understandable that someone gets something wrong — they’re not a doctor; they make a mistake. But we’re seeing purposeful disinformation leading people astray. We did a measles story because disinformation and a lack of faith means that people aren’t getting their kids immunized and these diseases start to come back, and it can be devastating and deadly. We’ve already lost two children in Texas. It’s so unnecessary. There’s a purpose for some of what we put out there, as a public service announcement, and one of those is, Vaccines work.

Latest News

For Sale! 2016 Sea Ray 350 Sundancer – $180,000

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

Exclusive Fine Art Partnerships: Pierre Emmanuel Martin

Lemieux et Cie and Pierre Emmanuel Martin: A Harmonious Collaboration in Fine...

A Comprehensive Guide to the White Isle

Ibiza: The Vibrant Heart of the Balearics in 2024 Ibiza, the sun-kissed...

Roschman Sells Boathouse Marine Center to BlueWater for $16 Million

© Copyright – autocontently.com

Man United seals spectacular comeback to beat Lyon 5-4 and advance to Europa League semifinals

Manchester United’s season isn’t done yet. On a night of high drama...

Leave a comment