Early in American Psycho, Mary Harron’s blisteringly good adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s 1991 novel, Patrick Bateman walks us through a typical morning. The 27-year-old investment banker and possible serial killer strolls around his Upper West Side condo in a pair of white cotton briefs that match the place’s stark décor, his exposed musculature as sleek and defined as an action figure. “I believe in taking care of myself, in a balanced diet, in a rigorous exercise routine,” Bateman intones, accompanied by a pensive piano piece by John Cale. At the start of every day, Bateman informs us while doing sculptural stretching in front of some vertical blinds, he does a thousand stomach crunches while wearing an ice pack if his face is puffy. His skin-care regime involves a pore cleanser, scrub, alcohol-free aftershave (otherwise it’s drying!), two moisturizers, and an eye balm. The application of the herb mint facial mask, as well as everything preceding it, is a floor-to-ceiling window into the life of someone with a credit-card statement in the place of a soul, a man who describes himself as a void in the shape of a human as he slowly peels the dried gel off his face, eyes dead.

The image of Bateman being so memorably enshrined onscreen in this sequence is not supposed to be aspirational. But pull up TikTok or Instagram or Reddit and you can easily find your way into a digital rabbit hole of content that veers hilariously close to American Psycho in form, if not in intent. Men of varying degrees of jackedness publish personal schedules or make videos in which they claim to rise with the sun, if not well before it, in order to pursue what are presented as mornings of near-monastic discipline devoted to wellness, grooming, and work. Some of the basic elements have shifted — in 2025, we have enthusiastically embraced protein loading while leaning away from physical exfoliation — but the gist is pretty much the same. Bateman’s morning was meant to encapsulate the emptiness of his hypertrophied yuppie existence, all the consumerist effort that went into maintaining the immaculate shell covering up a brutality-fixated monster. And yet, separated from its satirical context, it might as well be an artful contribution to the grind-set genre. All that’s missing is a promo for Bateman’s life-coaching program and links for where to buy his preferred creams and supplements.

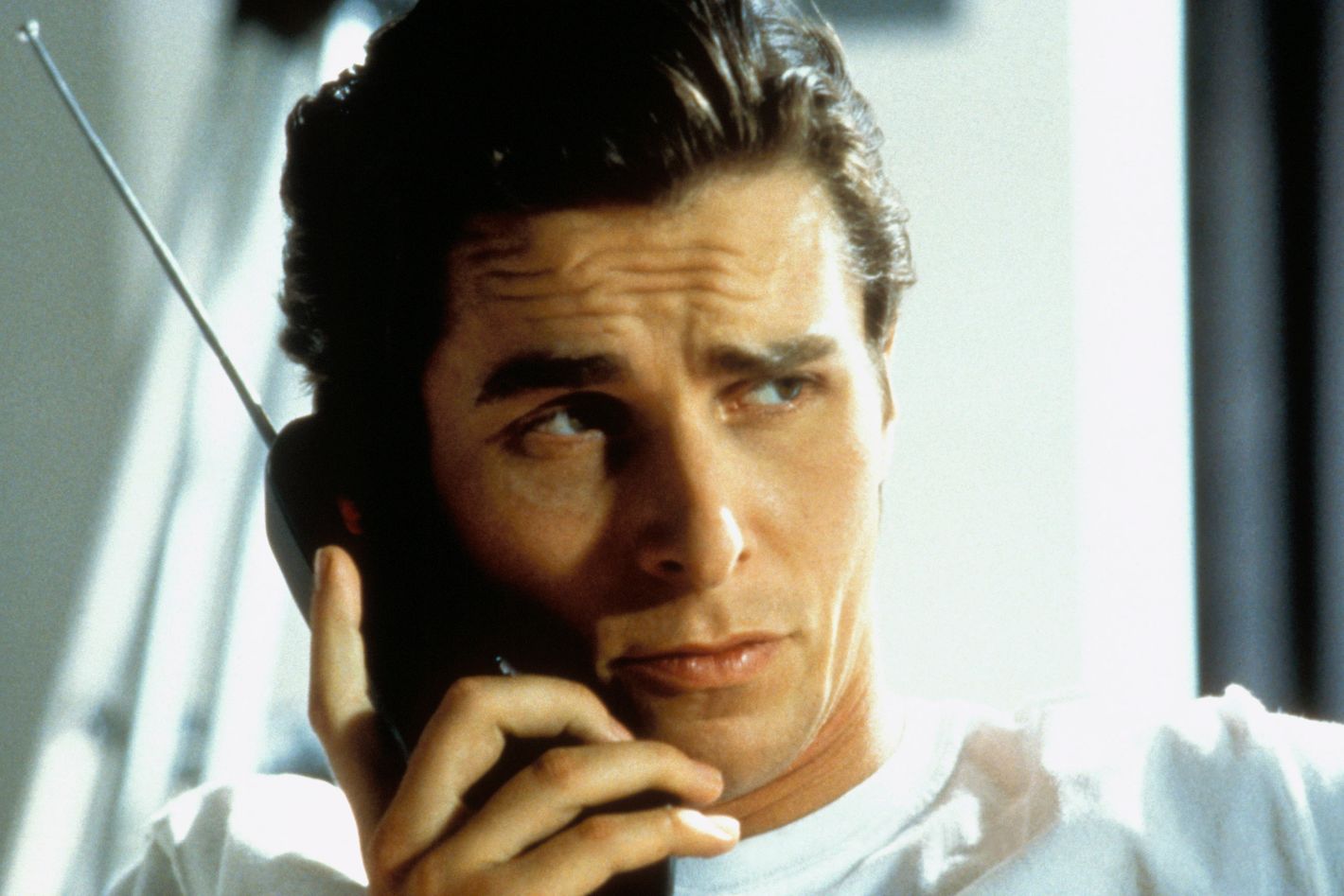

Has Patrick Bateman been given a sympathetic rebrand, or did culture just sink down to meet him where he always was? It’s been 25 years since American Psycho first hit screens, which, for the purposes of this journey, is an anniversary that matters more than the publication of the original book. Ellis conceived of the sociopathic Manhattan white-collar clone who’s so undeniable but interchangeable in his entitlement that he believes he really could get away with murder, whether the deaths he describes are just violent fantasies or not. But Harron gave us Christian Bale in his greatest performance to date, playing someone convinced he is only pretending to be a person and whose control over his own expressions is irregular enough that his ragged attempts at regularity would be obvious red flags in a world that wasn’t warped around him. In taking a character who’d previously only been experienced through claustrophobic first person, and rendering him in contoured flesh and convulsive expressions, she created a Bateman ripe to be stripped of meaning.

This wasn’t the fault of Harron, who understood the assignment entirely. She appreciated, in a way that Ellis and some fans of his book at the time did not, that the material would become more satirical onscreen, its combination of brand recitations and blood-soaked brutality more bitterly funny than nihilistic. “What I loved when I read the book was I thought this was early Evelyn Waugh, like around Vile Bodies. It’s so precise on these privileged people — getting the way they speak,” she told Vulture around the film’s 20th anniversary. Ellis was writing about an ’80s that had only just wrapped up, while Harron, with more distance, was making a recent period piece. Her Bateman is aberrant and hilarious, with his rictus grins and Master of the Universe styling, breaking into a rage-induced sweat at the sight of a superior business card and sounding as if he’s making fun of vapid urban professionals even when he’s being wholly serious. The irony is that while the character was a nightmare, he was also wildly compelling, which meant that overinvesting in him was inevitable. Like Walter White, he’s someone people couldn’t help but turn into an anti-hero, actual text be damned.

Unlike Walter White, Bateman was performed like a series of macros waiting to happen, which meant that Bale’s exaggerated expressions became the multipurpose stuff of memes. Over the years since Harron’s movie, pointing Bateman transformed into the face of gaming out double numbers on 4chan while grabs of Bateman holding up a Huey Lewis and the News CD, Bateman making a pained grimace while wielding an ax, Bateman flexing and pointing while engaging in a three way with two sex workers, and Bateman making an “ooh” became reliable reaction posts. The entire history of online culture is a cautionary tale about how little distance there is between ironic and real appreciation, and Bateman has always been a more malleable icon than most. He’s a real-life Crying Wojak, a Chad, and more recently, and not without some debate, one of the faces of the sigma male, a term invented by people who believe in hierarchies of masculinity but also know they’d never be assigned the tier they’d want.

Despite that online omnipresence, the rise of Bateman as a relatable icon does feel like it has more to do with how society has shifted than how our thinking about the character has. In the most literal sense, the American Psycho era is so back that there’s even a new Luca Guadagnino take on the book in the works. Trend forecasters have been touting the boom-boom aesthetic of shoulder pads and power suits and garish displays of excess while Donald Trump, ’80s tabloid fixture turned actual president, is back in the office. (The Bateman of the movie is less overtly worshipful of Trump than the version in the novel, though Trump’s 2016 claim that he could shoot someone in the middle of Fifth Avenue and not lose any voters was itself very Bateman-esque.) An American Psycho–inspired cocktail joint opened in Manhattan in March, named not for Dorsia, the impossibly exclusive restaurant that Bateman’s obsessed with getting into, but for the character himself. Bale’s Bateman has been held up as exemplary for his aesthetics — for that taut physique and that rigorous skin-care plan. Hell, his underfurnished apartment looks a lot like the anonymous monochromatic décor in the background of many an influencer video.

Has Ashton Hall, the guy who went viral for a TikTok depicting the supposed 5.5-hour daily morning routine that changed his life (and that involves mouth tape, a banana peel, and countless bottles of Saratoga Springs), ever seen American Psycho? Or did he arrive at a Bateman-style routine by himself, hustle-bro culture converging organically with Bale’s embodiment of sociopathic masculinity. It’s hard for the movie to register as a satire when we’ve wholeheartedly embraced so much about what it was making fun of, from the relentless consumerism to the unapologetic worship of self. The Bateman admirers who do know the film don’t seem oblivious to its conclusions, they just don’t seem to care. Looksmaxxing personality Kareem Shami, who hawks an online program promising to help young men improve their appearance through everything from skin care to mewing, goes by the handle “syrianpsycho” and told the New York Times that when he first encountered the film, he was inspired: “When I was watching it, I was like, Damn, I wish I had his skin-care routine, his morning routine. The only part that isn’t perfect is his psychopathic tendencies.” Justin Theroux, reflecting on his role as Bateman’s colleague Timothy Bryce, talked about his squeamishness about the degree of enthusiasm some people have for the character now: “In bro culture, he became sort of a hero, and I find that deeply disturbing.”

But it’s with failed bros that he seems to have the biggest imprint. On Reddit, users discuss relating to Bateman’s aloof inner monologues and defensively make fun of people who scold them for idolizing the character. Ron DeSantis, late in his unsuccessful presidential campaign, dropped a sweaty sigma-bait ad that included images of Bateman. We’re in a golden age of misreading, from Sam Altman wanting to brand his AI product as a real-life version of Her to Peter Thiel declaring that the only difference between Tolkien’s humans and elves is the latter’s immortality (and naming his data-analytics company after the books’ corrupting surveillance stones). But the adoption of Bateman as a role model is particularly telling, caught as it is between an act of joking and sincere appreciation, between self-awareness and delusion. It doesn’t feel like an accident that so many of the prominent figures who reference the characters, deliberately or inadvertently, are scammers selling various forms of life coaching. He’s someone whose appeal is a fundamental contradiction, this paragon of dominant manhood who’s both part of the power structure but who’s also alienated from and above it. He’s also a guy who has no real opinions of his own and who channels his frustration into rage-filled apocalyptic scenarios of violence against women, which actually makes him much more like a certain type of forum lurker than his fans would likely ever admit. The perfect bod and closet full of Valentino suits is optional — it may not be Dorsia, but theirs is a club that’s easy to join.

Related

Latest News

For Sale! 2016 Sea Ray 350 Sundancer – $180,000

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

Pope Leo XIV is a White Sox fan — and the organization is embracing the occasion

It’s the biggest victory for the struggling Chicago White Sox in a...

Jasson Dominguez hits 3 homers to lead the Yankees past the Athletics 10-2

Jasson Dominguez hit three homers and drove in seven runs to lead...

Ohtani hits 3-run homer in 9th to cap Dodgers’ wild comeback in 14-11 win over Diamondbacks

Shohei Ohtani hit a three-run homer to cap a six-run ninth inning...

Murray and Porter lead the Nuggets to a 113-104 bounce-back win over the Thunder

The Denver Nuggets knew bouncing back from their 43-point loss would mean...

Leave a comment