You may think of AI art as a form of machine-generated slop. But lately it’s been getting kind of weird. On April 21, New York’s senior art critic, Jerry Saltz, and the New York Times writer David Wallace-Wells held a conversation at David Zwirner gallery in New York on the subject. Among the questions they tackled: What exactly does AI art look like, and how is it that we can recognize it? Why has it proved so useful for political purposes, particularly as Trump-kitsch propaganda? How much difference is there between AI art and human art, really, and how long will that difference last? Here, an edited, condensed, and slightly remixed version of their discussion.

David Wallace-Wells: Recently, Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI and the sort of public guru of the AI moment, tweeted, “I think this is gonna be more like the Renaissance than the Industrial Revolution.” You tend to hear that kind of thing from people who think more about the Industrial Revolution than the Renaissance. But is it possible that the bigger disruption won’t be to the economy or the way we work, but the new forms, new feelings, and new meanings generated by AI?

Jerry Saltz: What you have to keep in mind about the Renaissance is that 90 percent of the art made then was bad. That ratio of quality may run through all eras and cultures. And so right now, I can say that 90 percent of AI art is going to be shite, and I know that is going to be true before it even happens.

DWW: I may be a little less interested in the question of whether it’s good or not than in just trying to figure out what it even is. I don’t even know what to call it.

JS: We have to call non-AI art just “art.” And AI art “maybe art.”

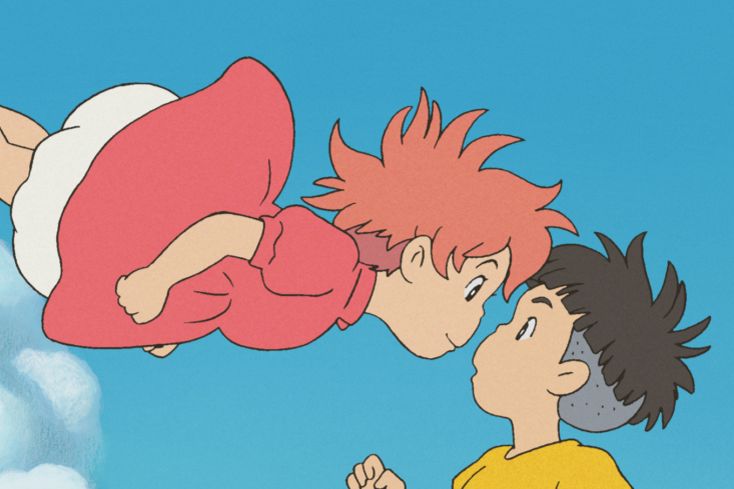

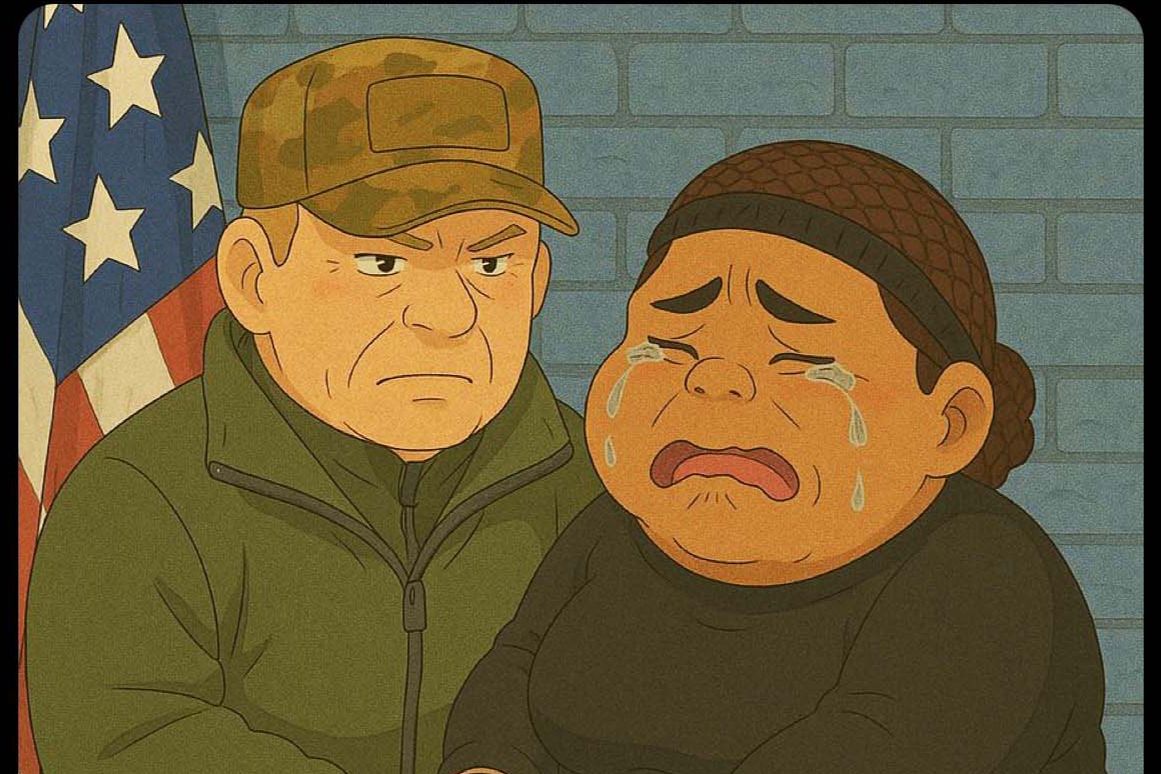

DWW: I used to think about these questions somewhat like Hayao Miyazaki, the legendary Japanese animator, who famously told a group of animators that he felt the whole project of AI-produced animation is “an insult to life itself.” But lately I’ve become less sure, partly because of the wave of AI-generated images made recognizably in Miyazaki’s own Studio Ghibli style — a whole genre of meme gleefully repurposing the aesthetic of a man who could not have denounced this sort of thing in more emphatic terms. And then the White House used the style to depict an arrest of a woman by ICE that would presumably lead to her deportation. This image stopped me in my tracks. Can you help me understand why?

JS: Well, in some ways, this is an image that is an insult to life itself. But that’s not really because of the image. It’s because of who produced it. You’re not seeing the horror, anxiety, and brutality — you’re supplying that. What you’re actually seeing is just a cutesy cartoon.

DWW: You say that to diminish the image, but I wonder if it’s possible to say the same thing to elevate it. We often talk about AI art as though the AI is not exactly an author, whose hands or intention you can see, but a kind of floating, nonspecific oracle. But one thing this image tells me is that AI art can have an author, whether we think of that as being Trump or Stephen Miller or the White House or simply the present political moment.

JS: Well, I think you’re right about that, and that brings you right up against ideas of copyright and plagiarism, too. Where did this come from? This is a recognizable act of appropriation and, in that sense, an artistic strategy.

DWW: That idea of strategic appropriation is comfortable enough for me if we’re attributing the strategy to a sadistic social-media intern. But I start to feel more unsettled when I think about authorship in terms of a disembodied machine intelligence.

JS: There’s a difference between AI as a tool for human expression — which would make it part of a category that includes all kinds of tools, from cameras to Photoshop — and AI as the entity that is expressing itself. There might be a machine intelligence, as you say, and perhaps that uncanny feeling we are experiencing when we look at AI art is the feeling of encountering the ghost lurking in the algorithm. But I don’t know if I can relate to that ghost in any way; I don’t know what its experiences are or if they even matter. Maybe its sensibilities are as rudimentary as those of a virus or a parasite.

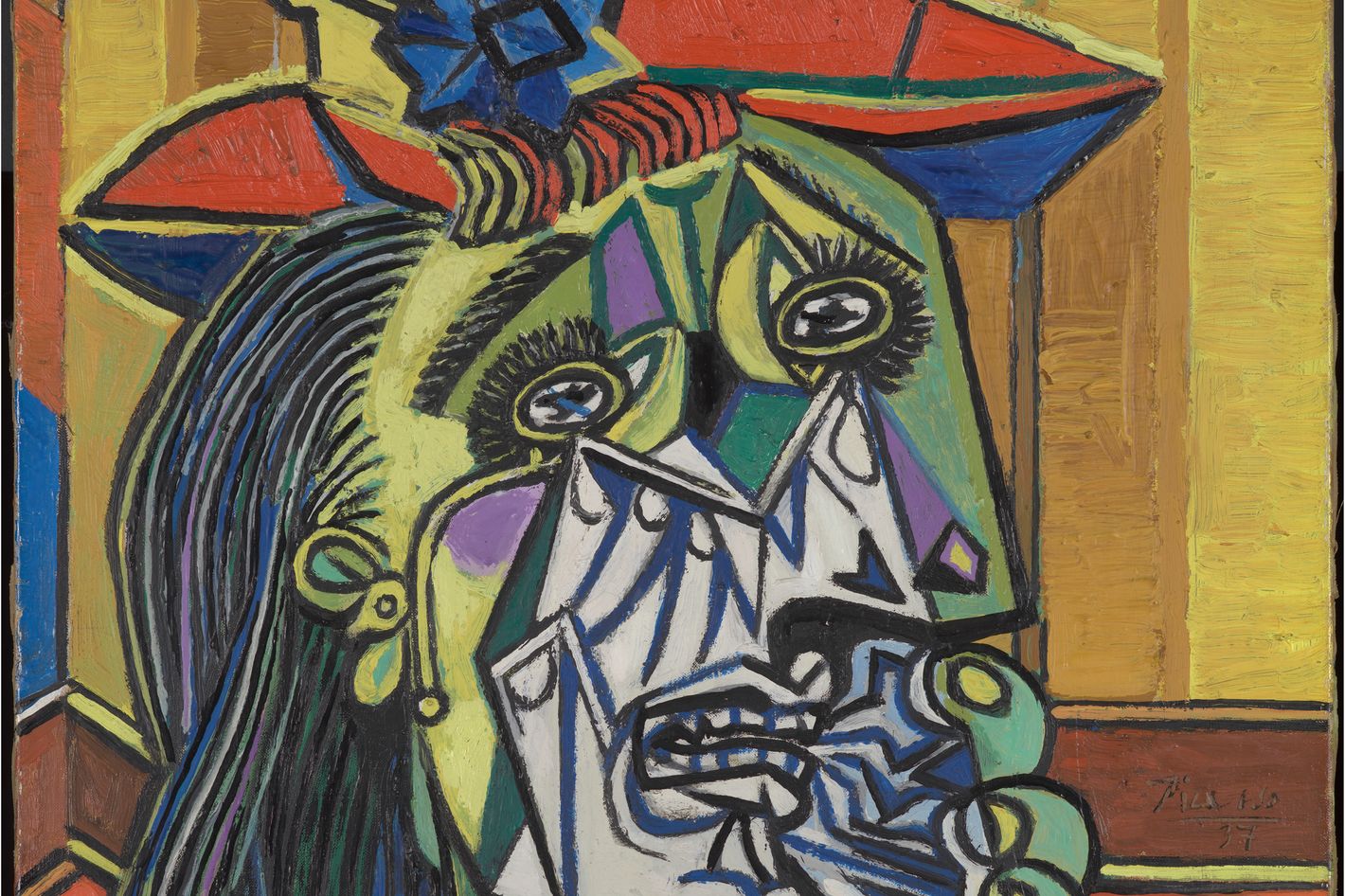

But let’s talk about some specific works. Here, we have one of the greatest paintings ever painted by Goya, a dog lost in the post-Napoleon deluge — post-death, post-destruction, a man’s best friend. And next to it is something I prompted AI to generate based on the Goya image.

DWW: The Goya is obviously a masterpiece. But are we sure yours isn’t valuable too? Are we sure we need to be thinking of it as something categorically lesser than? If so, why?

JS: Well, first, there’s the context — it came from nowhere and exists in no time.

DWW: Isn’t the context that Jerry Saltz in 2025 was trying to make sense of the world of AI and what it was doing to visual culture? That is pretty interesting context to me, even if it may prove very time-limited — who knows how long it will seem mind-bending that someone like you is doing experiments like these? Yet when I look at this image in particular, I don’t think I need to fold in the context of its creation. I just think, Those eyes are crazy!

JS: I didn’t intend this, though. (But then in my own writing, I never intend anything and it seems to come out.) And I would love to see this work in person. I’d love to know what materials went into making it. I’d love to know its scale. I’d love to know its surface. I’d love to know what was in back of it. None of that exists in my image. My image arrives like the Virgin Birth.

DWW: But there’s a lot of art that’s made through pastiche and digital manipulation. If you’re making a collage in Photoshop, there isn’t texture, there isn’t materiality. Most people would say that what doesn’t exist here is the hand of the artist. And one question that raises for me, maybe so fundamental it seems childish, is, How much of what we’re responding to when we’re responding to this painting is everything we know about Goya and his work, and how much is embedded in the image itself? And how is that balance different, or not, for AI art?

JS: Well, that’s a complicated question. In one sense, art is not about understanding. It’s about experience, something that happens to you when you look at it. And so, yes, it’s possible that AI-generated art could induce a similar experience merely from being looked at, with the viewer unaware that the work has no depth or history. But in another sense, art is about gaining understanding over time. The older I get and the more I learn, the more fully do certain works of art resonate with me, the more I appreciate the struggles of the person who made them and the times in which they were born. I’m not sure AI art can evolve in that way.

DWW: But other kinds of artistless art work that way on you, too. I think about the writing you’ve done about your almost-religious experience with cave art. In those moments, looking at those paintings, you can see the touch of a human hand — you know in some sense that a single person did paint it — but we feel it less as an individuated human expression than as a collective creation expressing something like an entire culture or civilization. In fact, that’s a lot of what gives it meaning.

I was recently in Egypt and had a similar experience in those ancient tombs, looking at hieroglyphics and paintings that were 4,000 or 5,000 years old — many of them much more colorful and elaborate than I’d expected. And what I felt in those moments was that while I knew these images were created by a single person, the experience I had encountering them all those thousands of years later was that I was sort of looking at something like “ancient Egypt” as a whole. That’s partly a fantasy — we’re looking back through history through a pinhole here. But the distance I felt from that world, and the unfathomability of what created these images, was also a huge part of what made it so powerful.

JS: That’s very true. In the caves, my whole world changed. I felt it. I learned from looking at those images that those were people who had studied mammals for 200,000 years.

DWW: Could you not say the same about AI, which has been trained on something like the whole corpus of human written and visual history?

JS: It may have been trained on that corpus, but it has no part in it. It doesn’t extend it. It has no experience beyond what we humans have already experienced.

DWW: I understand why that makes this different. Intuitively, I also understand why it can make AI uncomfortable, including for me. What I’m beginning to wonder is whether it doesn’t also make it, at least potentially, more magical. I recently read a beautiful passage on this subject by the pseudonymous writer Scott Alexander: “We gripe about how LLMs are destroying wonder, never thinking about how we’re speaking to an alien intelligence made by etching strange sigils on a tiny glass wafer on a mountainous jungle island off the coast of China, then converting every book ever written into electricity and blasting them through the sigils at near light speed. It’s all amazing and we’re bored to death of all of it.”

JS: Well, why shouldn’t we be bored? AI is really just the end point of post-post-postmodernism, an endless recycling and reinterpreting of stuff that already exists. One of the reasons it’s easy for the AI enthusiasts to poke holes in concepts like authorship and context is that the postmodernists laid the groundwork for them.

DWW: So if what we’re seeing in AI art is also the authorship of our whole visual culture, I wonder — what actually does constitute the AI aesthetic? Why is it that, so often, I know it when I see it? I have a few references in mind — there’s some American regionalism, there’s children’s books, there’s anime porn. What are the signal characteristics of AI art for you?

JS: I have a bunch. First, soft lighting.

DWW: Often from the front.

JS: There’s rigid symmetry, often looking like a Wes Anderson still.

DWW: One thing that’s interesting to me about that is the way in which a remarkably distinct and idiosyncratic visual style can so quickly become a generic trope. That’s not new to AI, exactly, but it’s not hard to imagine AI accelerating it — the rapid canonization of certain visual tropes.

JS: There’s what I call “the perfect face.” There’s candy-colored surrealism. Goth apocalypse.

DWW: The last one so closely matches a kind of genre of outsider art we know is bad — those heavy-metal paintings done on velvet you might see in a yard sale.

JS: Yes. We’re echoing nostalgia. And there’s those glitchy limbs.

DWW: The glitches are interesting to me. Most of the other characteristics you’ve identified are examples of the AI, on some level, giving us what we want — what we like.

JS: Who doesn’t love all of these images made of other images?

DWW: Or other moods, familiar and happy moods. But the glitches are something different — evidence of AI failure.

JS: And you like that?

DWW: Well, I process it as uncanny. And I’ve learned from you over the years that some feeling of queasiness, of being unsettled, is probably a sign of something good — your brain is trying to make sense of something but failing to.

JS: Is being uncanny enough on its own? Is the sum of the artistic experience being disturbed and creeped out?

DWW: I remember you making the case to me about Jordan Wolfson by saying it was!

JS: But is this the same thing? If an AI can’t do hands and feet, it probably will be able to in six months. And maybe, then, we’ll look back and fetishize these problems.

DWW: I’m imagining some distant future intelligence, artificial or otherwise, surveying the whole sweep of human visual history, coming to this period in the mid-2020s and being confronted with so many images of what appear to be weird birth defects, and thinking, What happened? Was there some kind of nuclear accident?

JS: But these images will be long gone. They almost don’t exist the second they’re made. That’s their lifespan.

DWW: Once you’ve scrolled, they disappear. But being designed to disappear is also an artistic strategy, right? I think of Felix Gonzalez-Torres giving out candy.

JS: Yes, though you do always have to replenish that damn candy.

DWW: What about existing art? Does AI make us reconsider things we’ve liked in the past? Take Christian Marclay’s The Clock. In many ways, it’s a rule-based work. It’s all found material. It’s somewhat random, though in certain ways very intentional, in a way that isn’t always central to the experience of watching the film itself. It’s all references to things outside the work rather than things internal to the work. It is not really expressing much if anything about the artist’s own anything. It may be telling us about the experience of time. It may be telling us something about our visual culture through Hollywood over the decades. But it is also something that I could imagine being done now in exactly the same way with AI. And what I wonder about is whether I would now not be moved by that same work.

JS: The thing about The Clock is that it took virtuosic talent to make. It is an expression of human ingenuity. It returns us to that moment of looking at a Rembrandt or a Vermeer for the first time and thinking, How on earth did he do that? How did he come up with that? It expands the horizons of what I, Jerry Saltz, can do. A machine can’t do that.

DWW: But what should we make of artists whose work strikes us in retrospect as being AI-like?

JS: Well, remember, Vermeer disappeared for centuries and then he seemed to be important to us again. This happens.

DWW: You mentioned Wes Anderson earlier, and I do think it’s telling us something about our collective cultural veneration that it is spitting back so much stuff that looks like his work. Or take someone like Fernando Botero.

JS: In fairness, the art world has had a hard time with Botero.

DWW: Well, take someone like George Condo — is his work not like feeding Pablo Picasso prompts into an AI?

JS: All art comes from other art. All artists use other artists’ work.

DWW: I’m not trying to disparage it.

JS: The only thing as mysterious and complex as the whole universe is our brains, and we just don’t know yet what’s going to come out of it.

DWW: Let alone these new kinds of brains we’ve just built.

JS: Maybe when AI starts having sex and fears death, it will start making great art.

Latest News

For Sale! 2016 Sea Ray 350 Sundancer – $180,000

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

Trump’s Acceptance of Qatari Plane May Present National Security Risks: NPR

The Controversial Gift: Qatar’s Offer of a Luxury Aircraft to Trump On...

Struggling Sergio Garcia says he’d decline playing for European Ryder Cup team right now if invited

Sergio Garcia has appeared in 10 Ryder Cups and amassed more points...

Arsenal secures return to Champions League on day of farewells for Everton and Vardy

Arsenal has sealed its place in next season’s Champions League. Nottingham Forest...

The NBA’s final 4 is set: Thunder, Knicks, Wolves and Pacers remain, and parity reigns again

The parity era continues in the NBA. The New York Knicks haven’t...

Leave a comment