Not three years ago, David Cronenberg sent another unprepared festival audience sprinting for the exits. His Crimes of the Future, a distinctly anatomical vision of the world to (hopefully not) come, was just a little too gross for some of the more squeamish attendees of the Cannes Film Festival. Business as usual, you might say, for a director who’s been upsetting delicate sensibilities since his cult-shocker salad days of the 1970s, when the so-called Master of Venereal Horror earned himself the title. All the same, what staying power! How many of the man’s peers in the stomach-churning game are still churning so reliably after 50 years? At 82, the artist also nicknamed Dave Depraved still makes movies like a sicko half his age.

Not that Canada’s most prolific and divisive auteur has been going door-to-door to shock this whole time. In fact, part of what marks Cronenberg as one of the most exciting voices of his filmmaking generation (or any other) is a general refusal to rest on his laurels or his bad-boy reputation. Appropriately for a director so obsessed with transformation, he’s constantly reinvented himself along the way. His filmography is a history of violence, yes, but there are distinct periods of that history: It’s a zigzagging line that connects the scrappy titillation of Shivers to the revered Hollywood horror of The Fly, the scandalous art-house provocation of Crash, and the unlikely prestige recognition of what you could call his Viggo era. What all his films have in common is an intellectual curiosity as fierce as the carnage. From the shaky start (and much to John Carpenter’s chagrin), Cronenberg has always been the thinking man’s purveyor of sleaze and slither.

Does his new movie, The Shrouds, denote the end of one age or the start of another? It’s an unmistakably eulogistic affair — Cronenberg’s good-bye to the woman he loved for nearly as long as he’s made movies. Whether it ends up shutting the coffin on that half-century career of sex, death, and the sticky places where they meet remains to be seen. Something tells us that the octogenarian director wouldn’t be bothered by such morbid speculation, though he might think less warmly on the list that follows. Even a maestro of disgust could feel nauseous seeing his life work ranked.

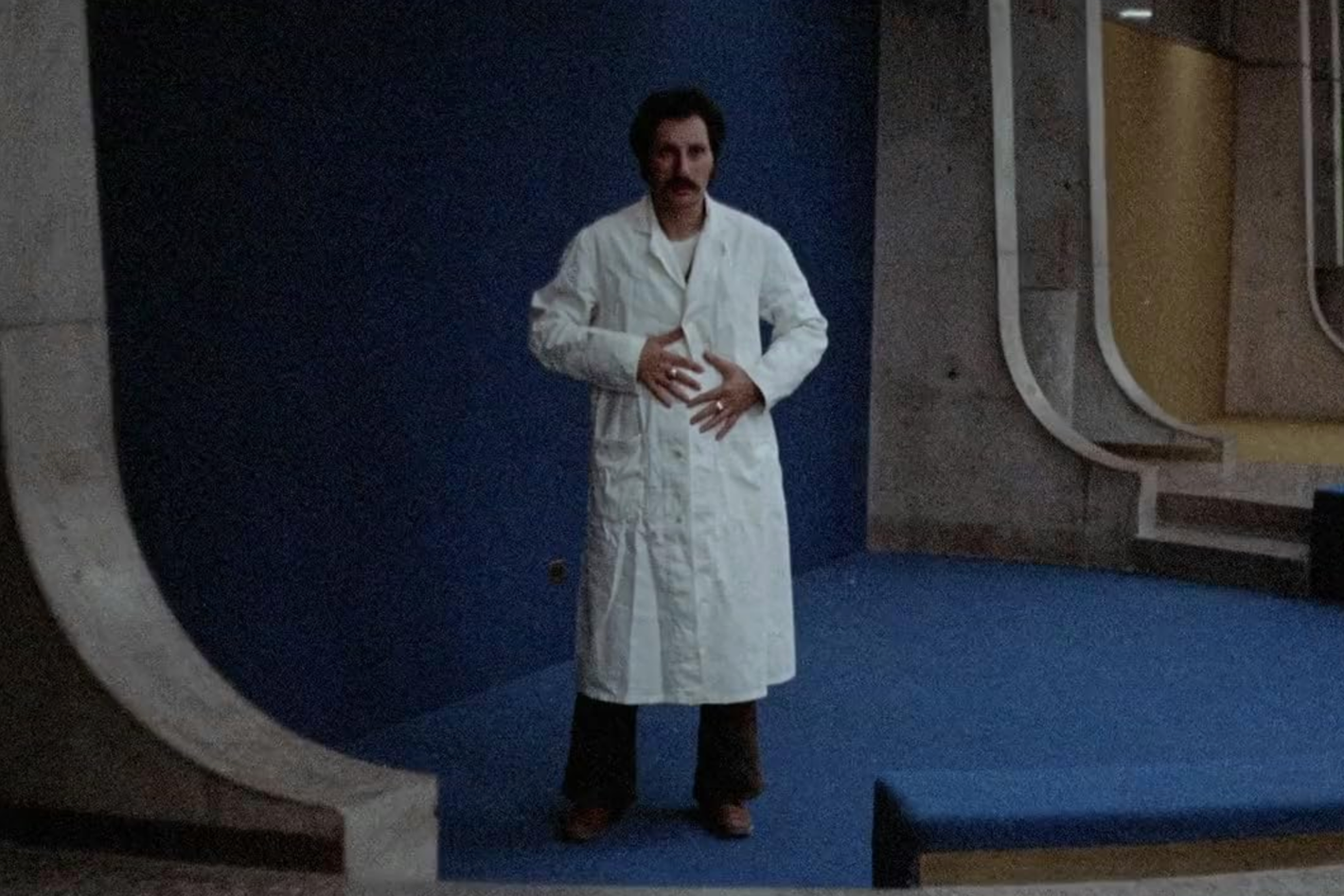

Stereo (1969) and Crimes of the Future (1970)

You can trace the ropy umbilical cord of Cronenberg’s obsessions all the way back to his first two features: a pair of hour-long sci-fi curiosities he shot cheaply and without sound on the campus of his alma mater, the University of Toronto. Presented as an academic study of destructively codependent telepaths, Stereo is basically a dry run to the later Scanners, emphasis on the dry. One year later, Cronenberg switched to color but kept the stiffly informational voice-over with Crimes of the Future, a dystopian drama so pregnant with offhand Cronenbergian concepts — including one he’d develop into a full feature of the same name some 40 years later — that it almost functions as premature self-parody. What the director hadn’t learned at this embryonic stage was how to bend his perverse preoccupations into a compelling dramatic shape, or even into gross-out thrills. Thesis films in the purest sense, they dully meander through the lecture hall of his already warped imagination. Only curious completists need enroll.

Fast Company (1979)

By contrast, there’s barely a hint of Dave Depraved’s sensibilities in this ramshackle drag-racing flick, a very different kind of B-movie than the kind he was otherwise making in the 1970s. Though something of a bona fide gearhead (he’d convert his love of cars into controversy a couple decades later with the icy-kinky Crash), Cronenberg is firmly in work-for-hire mode with the story of an aging driver (venerated stuntman William Smith) fending off retirement with the help of a ragtag pit crew of fellow rapscallions. Not without its very minor, even vaguely Altman-esque hangout-movie pleasures, Fast Company sputters around in second gear for most of its blessedly brief 91 minutes. Cronenberg has called it his least personal movie; it’s the only one you might never guess he directed and is about as justly forgotten as the knockoff Bruce Springsteen anthems that play on repeat throughout.

Rabid (1977)

Nearly killed in a motorcycle accident, a young woman (adult-film star Marilyn Chambers) receives an experimental surgery that transforms her into a 20th-century Typhoid Mary, unleashing a zombie plague via a pulsing stinger in her armpit. It’s Cronenberg who undergoes the true metamorphosis here; right from the opening scene, he exhibits a newfound clarity and confidence behind the camera. But if Rabid was a major formal leap forward for the director, it also plays like a sillier, less unsettling retread of his earlier Shivers, which had the good sense to confine its eroticized gloss on Night of the Living Dead to a single besieged apartment complex instead of opening it up to all of Quebec. Whether the film gets under your skin may depend, ultimately, on how you feel about its star, who’s either spookily unaffected or just kind of amateurishly blank in her first mainstream-movie role.

Maps to the Stars (2014)

Four decades into his career, Cronenberg finally shot a movie in Hollywood. Of course it turned out to be a withering takedown of Hollywood, depicting showbiz as a literally inbred circus of narcissistic stars, phony self-help gurus, and foulmouthed brat sociopaths. Sound painfully familiar? The script by Bruce Wagner (Scenes From the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills) was reportedly first written in the 1980s, which helps explain the moldiness of its insights. Thankfully, Cronenberg is less interested in taking potshots at his vapid characters (played by the game likes of Julianne Moore, John Cusack, and Evan Bird channeling Shia LaBeouf) than in unearthing the sadness and madness that gnaws at their superficial dreams. It’s a losing battle, but here and there, the movie threatens to become more nightmare than satire, like if an episode of Entourage suddenly mutated into Mulholland Drive.

Eastern Promises (2007)

Following the success of A History of Violence, Cronenberg reunited with Viggo Mortensen for the most expensive film of his career — and, in many respects, the most conventional. There are moments of signature grotesquery in this London-set crime thriller, which features slit throats, lobbed-off fingers, and one spectacular naked knife fight in a sauna. But as in Maps to the Stars, Cronenberg wrestles mightily with a mediocre screenplay he didn’t write, this one by Steven Knight, who builds his whole tale of underworld intrigue around an audience-surrogate heroine (Naomi Watts’s investigating midwife) completely inessential to its trajectory. Viggo, though, is terrific in his first Oscar-nominated role as a hoodlum climbing the rungs of the Russian mob while keeping his true motives concealed. Through the prism of his performance, Eastern Promises flirts with a deeper portrait of total psychological reinvention — the subliminal theme that must have drawn the director to such ordinary material in the first place.

Spider (2002)

“Restraint” is not a word that often leaps to mind while thinking of this particular filmmaker’s generally grisly oeuvre. But it’s appropriate for his ghostly quiet adaptation of a Patrick McGrath novel about a schizophrenic patient (Ralph Fiennes) wandering a decaying London while hopelessly, helplessly attempting to untangle a web of traumatic childhood memories. By placing us inside the scrambled thoughts of his lost, frail protagonist, Cronenberg casts constant suspicion upon the line separating past and present, via the visual and editorial equivalent of unreliable narration. Spider may lack the gory, squirmy immediacy of his most beloved work, but there’s plenty of horror to its portrait of a man unmoored from his own sense of reality. The film splinters the mind as pitilessly as previous Cronenberg movies went to work on the fragile, spongy body.

The Dead Zone (1983)

From Burroughs to Ballard to DeLillo, Cronenberg has an uncanny knack for adapting supposedly unadaptable novelists. So it’s a tad ironic that he’s nearly defeated by the structural challenges of a Stephen King best seller. On screen, King’s tale of a Maine schoolteacher who awakens from a coma with the blessing/curse of second sight becomes a rather episodic potboiler; without the book’s parallel portrait of a rising political monster, there’s a “case of the week” quality to Johnny’s adventures in mournful clairvoyance. Maybe these two masters of horror are just an imperfect match. All the same, Cronenberg gives the material an appropriately wintry melancholia, while coaxing an iconically intense (and quotable!) performance from his star, Christopher Walken. Say it with us now: “The ice … is gonna break!”

Shivers (1975)

Local critics were outraged by the movie that put the Master of Venereal Horror on the world-cinema map. What was the government thinking, they shrieked, tossing taxpayer money at this obscene creature feature about a parasitic slug that turns the residents of a Montreal apartment building into lusty ghouls? Not that there’s anything remotely extravagant about a schlock programmer whose amateurish acting and sparse production values betray its shoestring budget. But that’s all part of the DIY queasiness of Shivers (a.k.a. The Parasite Murders, a.k.a. They Came From Within, a.k.a. Frissons), whose eventual orgy of sexual violence is all the more unsettling after the rather, well, Canadian public-access qualities of the opening stretch, before everyone goes nymphomaniacal. Even at the larval stage of his career, Cronenberg knew how to make our flesh crawl and to scandalize the scolds.

Scanners (1981)

Forced to select the single most iconic scene or even shot of Cronenberg’s career, we’d probably reach for the moment in Scanners when Michael Ironside’s villainous Revok causes a rival psychic’s cranium to go kablooey. Originally intended to serve as a cold open, this incredible special effect proved so shocking to test audiences that they never quite got over it, compelling the filmmaker to drop it a little later in the movie. The funny thing is that, wild gore aside, Scanners is one of his most accessible films — essentially Cronenberg’s version of an X-Men picture, pitting the good and the evil Scanners against each other via close-ups of the actors grimacing and furrowing with silly mental concentration. Today, it looks like a breezy outlier in a more severe filmography, and good fun despite way too much of its wooden lead and way too little of Ironside’s fearsome heavy.

M. Butterfly (1993)

“If there was ever a film of mine that you could call a sellout, it was M. Butterfly,” Cronenberg once said of his most misunderstood movie. Certainly, the director had never made anything quite as … reputable as this handsome, sweeping adaptation of David Henry Hwang’s hit Broadway show about a French businessman seduced by an opera singer in 1960s Beijing. Whatever his motives, though, it’s a much more interesting (and characteristically perverse) melodrama than what scathing reviews described, thanks to a complexly unsympathetic performance by his Dead Ringers star, Jeremy Irons. The rub for many critics was a climactic twist easier to keep hidden onstage than onscreen. What too few asked was whether we were meant to realize what’s going on sooner than Irons’s besotted suitor, a man blinded by his romanticized, Orientalist fantasies. The transparency of the truth is the whole point of a movie about seeing only what you want to see.

The Shrouds (2024)

Consumed by heartache after the death of his wife of 43 years, Cronenberg embarked on his latest and possibly most achingly personal project. Vincent Cassel plays his proxy, a bereaved businessman who’s devised a morbid new innovation: a coffin webcam that allows survivors to monitor the ongoing decomposition of their loved ones. The Shrouds was originally conceived as a Netflix series, and there are hints of those origins throughout, including a plot whose convoluted corporate intrigue seems slightly better suited to serialization. But the central conceit is almost unspeakably moving in its deranged, borderline necrophiliac way (Cassel’s mourning mogul can’t bear the thought of not knowing what’s happening to his wife, even after death), and Cronenberg is savvy enough to spike his lament with a little self-critique. Like the man onscreen, he’s found a way to exploit his grief.

The Brood (1979)

Decades before eulogizing his second wife in The Shrouds, Cronenberg issued a far less tender good-bye to his first. Inspired by the acrimonious dissolution of his marriage (and, hilariously, his irritation with the sentimental reconciliations of Kramer vs. Kramer), The Brood is a bilious divorce movie for the ages. Samantha Eggar plays a disturbed woman who brings monsters to a custody battle, manifesting her resentment as pint-size rage babies that threaten her daughter, her ex-husband, and anyone else who gets on her bad side. Of course, it’s Cronenberg who’s really channeling his anger. Much more disturbing than the scenes of pint-size assassins wreaking havoc (or emerging bloody from a birth sack in the Grand Guignol climax) are the toxic emotions that inspired them. Plenty of his movies reach a climactic stage of post-humanity. This one remains uncomfortably human, at least in the unflattering post-breakup hostilities it expresses.

eXistenZ (1999)

The Matrix had been out for less than a month when along came a much gooier plunge down the virtual rabbit hole. Working from his own script for the first time since 1983’s Videodrome (to which this mind-bender plays like a spiritual sequel, just with the media obsession shifted from channel surfing to gaming), Cronenberg slow-runs Jennifer Jason Leigh and Jude Law through a deliberately convoluted joystick noir. His icky organic take on the digital future, a Luddite open world of bone pistols and nippled controllers, vacuum-seals eXistenZ in a way some semblance of real technology never could. That the game within the movie seems more chore than blast is a great joke that proved prescient, foreshadowing a future of immersively tedious sandbox MMORPGs. The closing line is equally prognostic; there’s even less telling these days where the game ends and real living begins.

Crash (1996)

Any fear that a splashy debut at Cannes meant Cronenberg was losing his edge must have dissipated the moment Crash crashed into the Croisette. His take on the J.G. Ballard novel inspired walkouts and jeers — a callback to the moral panic that greeted his early horror films, directed this time at an NC-17 blue movie about people turned on by automobile accidents. Crash is a hard thing to love; at times nearly plotless, it plays like a pornographic anti-porno, with sex scenes filmed as slickly and dispassionately as showroom footage. But there’s an integrity to its erotic tedium and the way it traps us as surely as the characters are trapped by their own transgressive desires (and maybe by the formative traumas that provoked them). By the way, only in the pre-web era could you make the claim — as Roger Ebert and other critics did — that no one could possibly be attracted to car crashes. If that fetish somehow didn’t already exist, Cronenberg likely created it with Crash.

Cosmopolis (2012)

No one writes dialogue like Cronenberg — perplexing alien dialogue, a sci-fi tongue of oddball terminology and metaphysical shop talk. That gift for singular gab made him an ideal fit for the work of postmodern novelist Don DeLillo, whose characters also speak in a stylized manner, in repeated and sometimes absurdist turns of phrase. Cronenberg borrows pages of such exchanges in Cosmopolis, starring Robert Pattinson as a young billionaire cruising across Manhattan in a stretch limo, witnessing the implosion of his financial empire — and by extension, the global economy — with a cool, nearly sociopathic indifference. The deliberately stilted tête-à-têtes, many of them unfolding in a plush coffin on wheels, get at how capitalism has rewired the basics of communication itself. And just as DeLillo seemed to spookily foreshadow a financial collapse on the horizon, so did Cronenberg somehow make the perfect apocalyptic allegory for 2025, a time when rich oligarchs are shrugging off their own senseless blitzkrieg on the dollar.

A Dangerous Method (2011)

Given the psychodramatic bent of his work, it’s no great mystery why Cronenberg was eager to dramatize a significant chapter in the early-20th-century lives of Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender), Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen), and Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley). What’s harder to discern is why so many mistook the results for something stuffy instead of a sharp, stealth comedy about the irrationalities of the supposedly rational. Beneath their air of irreproachable authority, Jung and Freud — both brilliantly played, the first with subtlety, the other with theatrical relish — wrestle with petty grievances and insecurities, while the former stubbornly rationalizes his affair with onetime patient Spielrein. Speaking of which, the movie opens like a monster movie, Knightley shrieking with uncommon volatility as her hysterical character is carted up to the institute in a carriage. A Dangerous Method has its biographical trappings, but it’s much too prickly (and funny!) to be filed alongside the glorified Wikipedia entries less adventurous filmmakers churn out when looking to real lives for inspiration.

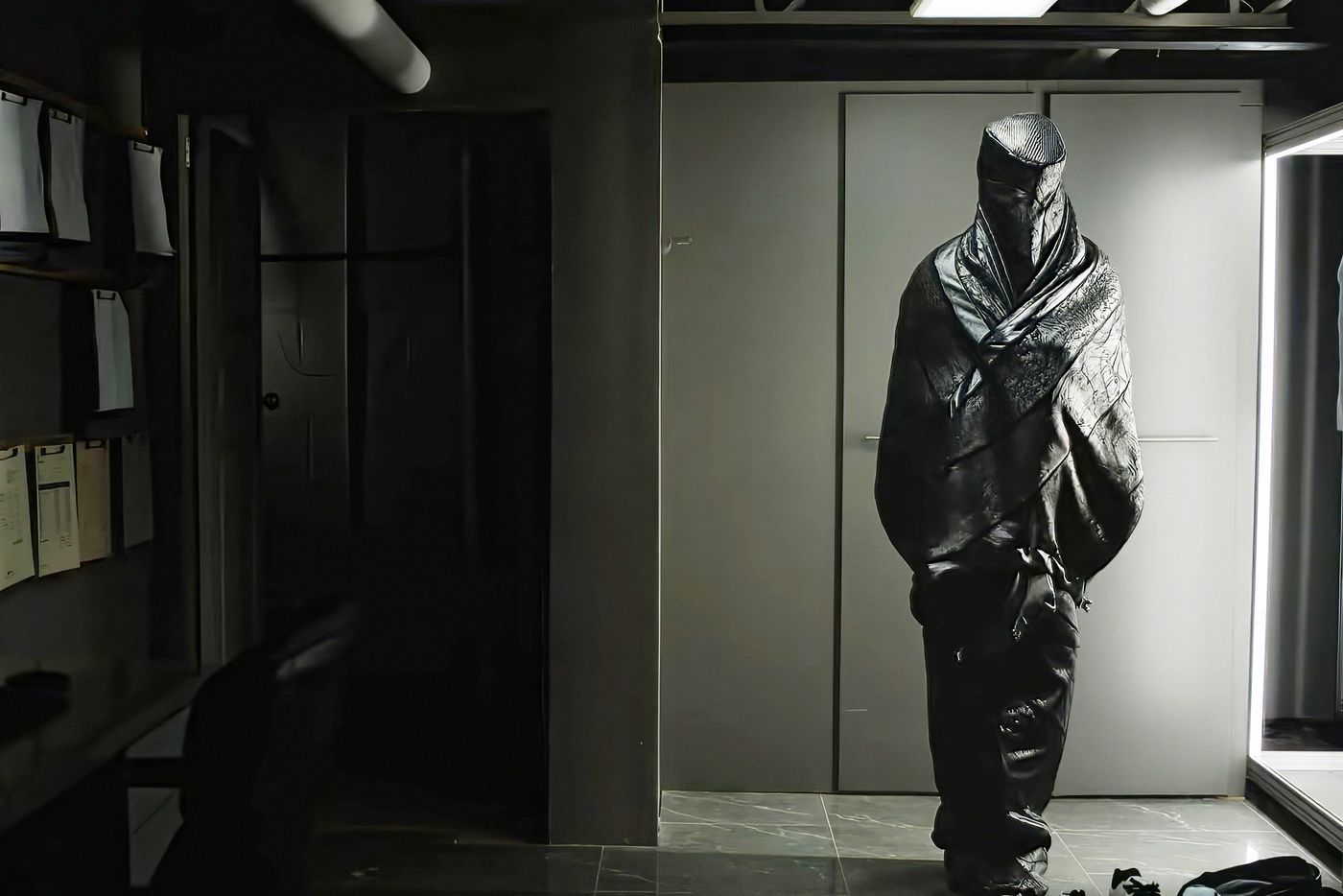

Crimes of the Future (2022)

In which our premier elder statesman of body horror returns to wryly, affectionately survey the state of the genre he pioneered and then put behind him. Repurposing the title of one of his earliest features, Cronenberg doesn’t so much go full circle as self-reflexively examine his own legacy via the futuristic tale of a performance artist (Mortensen, playing the director as plainly as Cassel is in The Shrouds) who specializes in fishing mutant organs out of his body. Set in a world where humans have begun to hideously adapt to the amount of plastic we’re flooding into the ocean, Crimes of the Future is bleak and repulsive on paper but oddly charming, even relaxed in execution. It’s also positively bursting with ideas — about the pretensions of the art world, about the expectations put on its legends, about what it means to share a life and career with someone. By the end, Cronenberg’s onscreen surrogate has reached a serene acceptance of the possibility that he’ll become something entirely new. It’s a good place for an ever-evolving visionary to land.

A History of Violence (2005)

Which brutality do we reject as a society, and which do we celebrate? That’s just one disquieting question posed by Cronenberg’s tense, acclaimed crime thriller, in which a virtuous family man (Mortensen, in the first of four fruitful collaborations with the director) finds his idyllic small-time life ruptured by the arrival of insinuating gangsters insisting they know who he really is. Hitchcockian wrong men, Eastwoodian gunslingers, Lynchian Americana, the killers of Hemingway and O’Connor: A History of Violence situates itself in an entire, well, history of violence of the page and screen. But as with its aww-shucks hero, there’s more to it than meets the eye; something much stranger lurks behind the slight Twilight Zone unreality of its very movie-ish Midwest. By the time the late William Hurt shows up as a soul-patched kingpin, regarding his “broheim” with amused incredulity, you start to wonder if Cronenberg is taking the piss out of the very archetypal yarn he seems to be spinning. The grim laughs come harder than the grimaces, thwarting any attempt to take the movie at (mutilated) face value.

Naked Lunch (1991)

Before there was Charlie Kaufman, we had this dizzying meta film, a box-office flop too antagonistically weird for the multiplex. Rather than try to reproduce every arguably arbitrary plot point of its William S. Burroughs source material, Naked Lunch aims for the bugfuck spirit of that classic; marrying some of the more outré plot points to details from the author’s life, the film becomes a backdoor biopic monstrously invigorated by its sci-fi metaphors. (Somehow, the portrait of a junkie writer looks new again when the junk is exterminator powder and the typewriters are sentient talking bugs designed by the great practical-effects artist Chris Walas.) Peter Weller’s deadpan performance as the Burroughs-coded William Lee, stumbling into literature by way of sci-fi espionage, holds the whole lunatic thing together. So does an ending that darkly equates creative and sexual awakening, while giving new meaning to the expression “kill your darlings.”

Videodrome (1983)

If Videodrome isn’t the greatest Cronenberg movie, it may well be the most Cronenberg. Psychosexual deformity? Inscrutable technological conspiracies? Grand proclamations like “the television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye”? All are present and accounted for in the reality-shattering odyssey of Max Renn (James Woods), a TV exec whose investigation into the broadcast of a mysterious snuff film has a profoundly destructive effect on his mind, body, and maybe soul. Whereas Videodrome could once reductively be described as a cautionary tale about the corrosive influence of television, its anxieties have only grown more trenchant. Isn’t there a dismaying relevance, in the age of YouTube and Fox News and Facebook, to the spectacle of a man radicalized by the dangerous media he consumes? That said, Max’s sea change is no more dramatic than that of the filmmaker, a merchant of grind-house thrills ascending to a new stage of creative maturity and boundless philosophical curiosity. Long live the new flesh. And the new Cronenberg.

Dead Ringers (1988)

When Jeremy Irons won Best Actor for Reversal of Fortune, he reserved a line of his Oscar acceptance speech for David Cronenberg, adding “some of you may understand why.” Anyone who saw him in Dead Ringers a couple years prior certainly did. Without exaggeration, Irons’s dual performance as identical twin gynecologists Elliot and Beverly Mantle is one of the great criminally un-nominated feats of modern acting; at nothing but a glance, you can tell which brother you’re watching … even when one is impersonating the other or after their personalities begin to disastrously blur. Dead Ringers, which marked a new peak of technical and dramatic sophistication for Cronenberg, has its moments of vintage corporeal unpleasantness (see, and never unsee, the instruments for operating on mutant women). But it cuts much deeper than the skin, tracing a wrenching downward spiral of codependency and folie à deux around Irons’s all-time tour de force.

The Fly (1986)

“Be afraid, be very afraid,” went the tagline to Cronenberg’s operatic mad-science masterpiece — still the biggest hit of his career some 40 years later. But fear is just one proper reaction to The Fly, which finds so much more than cheap thrills in the story of a brilliant physicist who accidentally merges his own DNA with a housefly’s. Moving a ’50s schlock object into the state-of-the-art ’80s was, of course, an opportunity to confront the audience with a vomitorium of upsetting sights, from peeled-off fingernails to inside-out baboons. Yet Cronenberg aims for the heart as heartily as the gag reflex: Thanks to the star-making chemistry between Geena Davis and Jeff Goldblum (the latter emoting richly under pounds of prosthetics to play the most sympathetic monster since Karloff’s), The Fly becomes a devastating meditation on terminal illness and the horror of watching a loved one waste away. What magic machine did Cronenberg consult to splice together such an audacious hybrid? His pinnacle is a Brundlefly itself, boldly fusing tragedy to the grossest shit you’ve ever seen in a Hollywood movie.

Related

Latest News

For Sale! 2016 Sea Ray 350 Sundancer – $180,000

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

World ranking chair Trevor Immelman says LIV has not reapplied and ‘the ball is in their court’

LIV Golf getting world ranking points would start with the Saudi-funded league...

MLB offense rises with temperature, batting average of .242 up from .240 through April last year

Baseball offense has picked up as the temperature has climbed in much...

Warriors return home to Chase Center with another chance to close out 1st-round series with Rockets

With his team trailing by 27 points to the red-hot Houston Rockets...

Scottie Scheffler returns to hometown Byron Nelson, takes 1st-round lead with 10-under 61

Scottie Scheffler is happy to be back at his hometown event and...

Leave a comment