This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

A stagestruck adolescent growing up in Washington, D.C., I had the same romantic view of Broadway from afar that every kid like me did back then — and maybe still does. A fantasy patched together from books (in my case, Moss Hart’s Act One), movies (All About Eve), and, with luck, family holiday trips to the big city to see a Big Broadway Smash. The Theater District I encountered when I moved to New York in the 1970s did not match that fairy tale. The neighborhood was blighted by prostitution, porn, and drugs; the city was facing bankruptcy; and suburbanites and tourists were shunning the sordid hellscape depicted in movies like Midnight Cowboy and Taxi Driver. Forty-second Street was now the Deuce. A Times Square marquee was more likely to herald Deep Throat than The Pajama Game.

In the 1960s, my parents thought nothing of letting me roam those same streets unaccompanied to take in the Camel billboard blowing smoke rings, the Automat, the extant movie palaces, and the pinball arcades. By the time I went to work at the New York Times as a drama critic in the early 1980s, the streets were so treacherous that the paper briefly hired a shuttle bus to pick up its commuting employees nightly from its old headquarters on 43rd Street to spare them the sleaze of the adjacent Hotel Carter, a hotbed of vice. The bus would then dump its passengers at the Port Authority Bus Terminal, where a fresh scrum of Eighth Avenue muggers and drug addicts was lying in wait.

You could argue that the world’s most fabled Theater District has continued steadily downhill ever since — sporadic, fleeting upturns notwithstanding. The decline continues. The truth about post-pandemic Broadway is that even as ticket prices have bounced back to exorbitant and unsustainable heights, commercial theater production is more of a fool’s errand than ever because the equally unsustainable costs of putting on a show can rarely be recouped no matter how high the ticket price. Meanwhile, the surrounding neighborhood is mired in homelessness, shuttered businesses, and marauding Elmos.

Paradise lost? Maybe not. When was there an idyllic Times Square, exactly? The historic fantasy of the Great White Way as a glamorous montage of gleaming marquees, sparky backstage romances, and elegant audiences reveling in black tie was a Hollywood concoction, arguably false from the start. The movie that first spawned it, the 1933 Busby Berkeley musical 42nd Street, was, like the Broadway stage adaptation a half-century later, a laundered version of its source material, an eponymous 1932 roman à clef by Bradford Ropes. In the novel, Broadway’s backstage is presented as a sweatshop commanded by sadistic directors and illiterate, penny-pinching producers, many of them sexual predators, who drive the performers and backstage crew to exhaustion and, in one instance, death. The neighborhood they toil in is rowdy and often tough.

Did Times Square make a comeback after that? The advent of sound in Hollywood six years ahead of the Busby Berkeley 42nd Street had already triggered a Broadway decline, knocking the number of new productions down to 174 for the 1932–33 season from its peak of 264 in 1927–28, when The Jazz Singer supercharged talking pictures’ usurpation of the stage as the foremost medium of American mass entertainment. As television caught on in the 1950s, the erosion continued. By the early 1960s, a typical Broadway season would field on average 60 or so shows. Even decades before the pandemic, that number had fallen into the 30s.

Over the course of those decades, the drop in theatrical production was not accompanied by a rise in Times Square gentility. I wonder now what my parents were thinking when they allowed the young me to wander the West 40s without supervision in the 1960s. The trade paper Variety, which then provided the most authoritative coverage of Broadway, published a page-one story in 1968 reporting that Times Square, “the hub of Manhattan’s show biz and site of famous real estate, has of late often been termed ‘Slime Square’ or ‘Crime Square’ ” because of its “slide from respectability to sleaziness to downright tawdriness,” with “girly pix” being sold to “kids” and “harlots now on duty 24 hours a day,” lined up “nearly solid” on 47th Street off Seventh Avenue. Granted, “girly pix” were not hardcore, but still.

Not that the ostensibly placid 1950s that preceded the anarchic ’60s were nirvana in New York’s Theater District. “Coney & B’Way: Shabby Twins” screamed a June 1956 Variety front-page headline over a story demoting both Coney Island and Times Square to “the great New York City entertainment beats of yesteryear” and portraying them as locked in a race “to see which is the shabbier.” Broadway was condemned as a “hey-buddy-wanna-buy-a-watch strip tease colony” and 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues as “carnival and commerce at its most depressing level with a cast of characters out of Dostoevsky, Algren, Spillane, and Gide.” (Perhaps the first and last time an American showbiz trade publication was provoked to name-check Dostoyevsky and Gide.)

Yet for all these sightings of Sodom and Gomorrah on Times Square, the Broadway shows running in 1956 included the original productions of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and My Fair Lady and in 1968 Cabaret and Arthur Miller’s The Price. There seems little, if any, correlation between Broadway’s cultural attainments and the surrounding urban depths in any given season. The theater’s artistic triumphs (in good seasons) and the raucous, even dangerous neighborhood (nearly every season) are both hardwired into the Times Square DNA.

That’s what I came to understand in my 13 or so seasons as the Times’ drama critic. I arrived at the job thinking I knew a lot about the theater. But it depended on how you define theater. There is the theater made by playwrights and actors and directors. But in New York, there has always been the theater business, as in producers and theater owners and press agents, all squeezed together in the hothouse neighborhood branded Broadway and integral to New York’s international identity since the Roaring ’20s. The business reality was literally in my face at the Times. I could look out the third-floor newsroom windows of the old headquarters and peer into the offices of the Shuberts across 44th Street. The Shuberts, then and now, have far more clout and far deeper pockets than those of any producer in the American theater. They own nearly half of Broadway’s commercial playhouses and almost all of the most desirable ones as measured by location, felicity of design, comfort, acoustics, and historical provenance. They are the most enduring and powerful force in the modern American theater, period. Their reign began early in the 20th century and has survived unabated into the 21st.

In a real sense, you could say the Shuberts and the Times invented Times Square. The two institutions’ histories were conjoined from the get-go. The Shuberts’ rise to dominance in American theater occurred on the same geographical turf and roughly the same timeline as the Times’ ascent to the peak of American journalism. In coincidental tandem, the families behind both enterprises, both of Jewish-immigrant origins and both interlopers from the provinces (the Shuberts from upstate, the Times clan from Tennessee), had been collectively responsible for colonizing Times Square since its birth.

They were in conflict almost from the start. The Shuberts were interested in profits. The Times liked profits too, but that meant sometimes publishing reviews and news stories that threatened the Shuberts’ bottom line. The first volley was exchanged in 1915 when the paper’s young critic Alexander Woollcott dared suggest that a Shubert attraction, a German sex farce titled Taking Chances, was “not vastly amusing.” (He praised its cast, but no good deed goes unpunished in theater reviewing.) The Shuberts responded by banning Woollcott from their theaters and refusing to advertise in the Times. The paper filed a suit that became national news; an appeals court reversed an initial decision in its favor, allowing for the ban. After a year, the Shuberts decided the Times’ advertising was worth more than the cold war. Woollcott, not yet 30, reveled in how the Shuberts’ stunt had backfired and made him famous: “They threw me out and now I’m basking in the fierce white light that beats upon the thrown.” These square-offs within the neighborhood’s tight confines would continue in perpetuity, the Hatfields and McCoys with the added wild card that these Hatfields and McCoys were ambitious, newly minted Jewish Americans, not hayseeds.

Adolph Ochs, the paterfamilias of the Ochs-Sulzbergers, moved north from Chattanooga after buying the failing Times from its previous owners in 1896. He revamped the paper editorially (“All the News That’s Fit to Print” was coined as a marketing ploy) and in 1905 moved its headquarters from the old Newspaper Row near City Hall to a new building uptown, the second tallest in the city, at the once-remote intersection where Broadway and Seventh Avenue crossed each other at 42nd Street. Ochs’s chosen piece of real estate was not yet “the Crossroads of the World,” as Times Square would later be known, but the gateway to Longacre Square, long a sleepy district of brownstone apartments, bordellos, and horse exchanges but now in the throes of redevelopment as an entertainment district. The Times insisted a central hub of the new IRT subway, Manhattan’s first rapid-transit system, be named Times Square Station. Ochs’s enterprise was so successful that he didn’t wait a full decade to erect the bulkier tower on 43rd Street that it was still occupying when I reported for work almost 70 years later. Even so, the Times held on to its old headquarters at One Times Square into the early 1960s, ensuring that a mesmerizing news “zipper” telegraphing the latest headlines in lights and a televised New Year’s Eve “ball drop” would become synonymous, like the neighborhood, with the paper’s name.

The three Shubert brothers, born in what is now Lithuania, were the sons of a peddler who migrated to America in the massive Eastern European immigration wave of the late 19th century — two generations behind the arrival of the German Jewish émigrés exemplified by the more assimilated, American-born Ochs. The Shuberts’ trajectory from poverty to showbiz royalty paralleled that of their contemporaries Louis B. Mayer, Adolph Zukor, and the Warner brothers, who pioneered the American film industry, first in the East, then in California. But just before moving pictures started to proliferate in their nickelodeon infancy, the Shuberts saw an opportunity in the legitimate theater and grabbed it. They cobbled together a small network of playhouses upstate and set their sights on usurping “the Syndicate,” a monopolistic empire that controlled the booking of virtually all New York shows on the road. Their main instrument of attack was a theatrical weekly they created but funded clandestinely, New York Review, that vilified the Syndicate with progressive-era trust-busting vehemence worthy of Upton Sinclair. With time, cunning, and no irony, the Shuberts slew the Syndicate Goliath and built a monopolistic empire of their own that Justice Department lawyers would decades later force into an antitrust settlement.

The first Shubert boy from Syracuse to migrate to Manhattan was the middle brother, Sam, whose foothold was a job managing the Herald Square Theatre in 1900. Sam was the canny Shubert, the vaguely artistic Shubert, the thought-to-be-maybe-gay Shubert. He died from injuries sustained in an explosive train wreck in 1905 at age 26, four months after the Times moved into its new tower. Prefiguring Hollywood’s memorialization of Irving Thalberg, the MGM studio chief who died at 37 in 1936, Sam was thereafter canonized as a “boy wonder” by his industry, his black-and-white photographic portrait enshrined for decades in the lobby of every Shubert house. The brothers he left behind, Lee and J.J., forged ahead. They eventually “owned more theaters, employed more performers, produced more plays, and probably bedded more chorus girls than any other producers in the history of the American theater” in the estimation of their definitive biographer, the cultural historian Foster Hirsch.

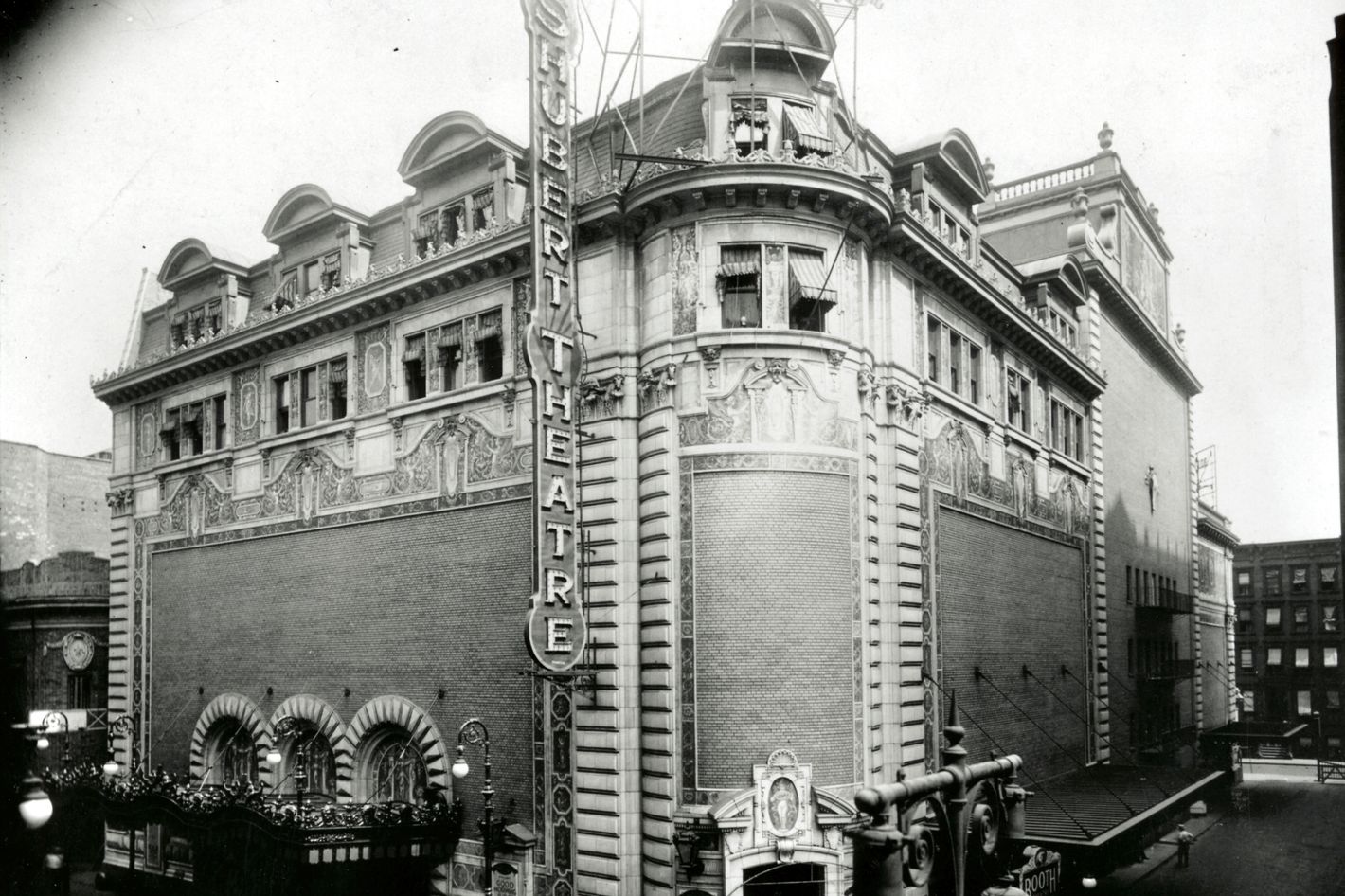

The empire grew from a single brainstorm of Lee’s in 1906, in which he envisioned an “uptown” Theater District at a time when theatrical activity was centered on Herald Square, eight blocks south of the new Times Square. Even as rival showmen were building their palaces on the grander boulevard of 42nd Street or Broadway itself, he saw a future of thriving playhouses along the side streets and gobbled up brownstones on the blocks between Broadway and Eighth Avenue from 44th to 49th Streets. The rowhouses were razed for Shubert houses, most of them open by 1923, with the last, the Barrymore, arriving in 1928.

Lee Shubert’s urban masterstroke proved as permanent as any real-estate coup can be in New York. Nothing else was brilliant about the sphinxlike “Mr. Lee,” as he was known. He spent undue hours in daily sunlamp treatments that made others liken him to a Jewish “cigar-store Indian.” He could barely read or write, and in the words of his younger sibling, J.J., he took no notes, kept no files, and was a thief who surrounded himself with other “crooks.” For his part, “Mr. J.J.,” as he was known, was a coarse bully whose rage and parsimony drove superstars of the day like Eddie Cantor, Mae West, and Fanny Brice to flee the Shubert fold. The brothers’ contempt for each other, a blood feud that ran longer than any attraction booked into their theaters, made it impossible for them to inhabit the same office. Instead, they glowered at each other from palatial suites across the gulf of 44th Street. Lee’s was an aerie at the top of the flagship Shubert Theatre, built in 1913, the same year the Times erected its second tower around the corner on 43rd Street. J.J.’s domain was the Sardi’s building, another Shubert property, where he maintained both his office and a penthouse home. He was moved there on his brother’s initiative in an attempt to isolate and marginalize him. Nicknamed in honor of the ground-floor tenant that began its long run as Broadway’s signature restaurant in the 1920s, the Sardi’s building shared a boundary with the Times’ back exit and loading docks. Each night, as diners swarmed in for a post-curtain supper, bundles of the paper’s first, or “bulldog,” edition would be hoisted into trucks for delivery up and down the Eastern Seaboard.

As the century moved on, the Times became a totem of middle-class culture and propriety. This was hardly the case with the Shubert empire. Not a single one of the Shuberts’ prolific productions — most of them vaudeville-centric revues and threadbare touring companies of tired European operettas — came anywhere near entering the canon of American entertainment, let alone American drama. The Shuberts didn’t just bed (and serially marry) chorus girls; they demanded sexual submission as a condition of employment. They also took a cut of the large cash bribes that scalpers paid corrupt Shubert box-office treasurers in exchange for prime tickets they resold at larcenous markups. The Shuberts thought nothing of sabotaging their own hit bookings if they spotted a potentially more lucrative new tenant on the horizon. Until they were caught in the act by its producer, they even tried to truncate the run of the original 1943 production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!, the longest-running musical in Broadway history at the time, apparently by withholding tickets from its box-office racks at the St. James Theatre so the grosses would drop low enough to trigger a contractually mandated eviction. Too avaricious to compromise their rigid financial terms, they lost the postwar gold mines Guys and Dolls and My Fair Lady to competitors.

Lee died in 1953, his brother J.J. a decade later. Their sole plausible successor, J.J.’s son, John, died suddenly at age 53 in 1962, a year ahead of his senescent father, who was never told of his death. Like his long-deceased uncle Sam, John died on a train — of a heart attack, in a private car heading to Clearwater, Florida, en route from New York. In keeping with the family tradition, the final Shubert scion had also produced nothing of consequence. His few long-ago credits were typified by Hold Your Horses, a musical revue he mounted at the Winter Garden in 1933 and where he met his wife, cast as a “Dancing Girl.” When modern theater artists crossed his path, John Shubert refused to work with them, dismissing Elia Kazan as “an animal” and Tennessee Williams’s plays as “an effeminate type of work.” If only because he spoke publicly of addressing Actors’ Equity’s long-held complaints about the overflowing toilets and rampaging rodent populations of Shubert dressing rooms, John struck some Broadway denizens as a Kennedyesque prince compared with J.J. and Lee. His funeral was held on the stage of the Majestic, where the set of Camelot was draped in black velours. His will had stipulated that the obsequies be confined to a non-matinee day to avoid sacrificing any ticket sales and that his widow sit in a chair next to his coffin and a lectern on an otherwise empty stage throughout the bleak farewell. He bequeathed her the bulk of his estate.

Though John was the last direct heir to the Shubert brothers, I discovered upon joining the Times nearly 20 years after his death that the executives who now ran the business were nonetheless called “the Shuberts” and regarded as omnipotent like their predecessors. The usurping Shuberts, named Gerald Schoenfeld and Bernard Jacobs, occupied Lee’s sumptuous quarters above the Shubert Theatre. The empire had been rebranded with an august moniker, the Shubert Organization, and was owned by an entity called the Shubert Foundation, which meant that the city’s most lucrative playhouses and large swaths of midtown’s most valuable real estate were rewarded with tax breaks befitting a nonprofit. The Shubert Foundation claimed to have been conceived by J.J. before his death as “a charitable organization for the poor and helpless.” This landed as a sick joke among the brothers’ contemporaries, given that J.J. and Lee were notorious misers whose wills stiffed not just relatives but many of the underpaid drivers, valets, and secretaries who had been their loyal indentured servants since time immemorial.

By the time I entered the fray, those who worked in the New York theater and most journalists who covered the industry were foggy at best about how Schoenfeld and Jacobs had attained their positions and how their ruthlessly profitable business merited the status of a foundation. Ludicrously enough, the president of Columbia University sat on its board alongside John Shubert’s alcoholic chorus-girl widow.

The new Shuberts were simply “Gerry and Bernie.” Their faces could pass for the masks of comedy and tragedy in repose. Gerry, round and bald, was the ebullient front man who declaimed with a booming voice and orotund diction suggesting he was a product of the Barrymore acting royalty rather than DeWitt Clinton High in the Bronx. His longtime friend Bernie, slight, dour, and prone to terse stabs at gallows humor, was the deal-maker. Before joining Shubert, Bernie had been a lawyer in New York’s Diamond District. Even when he engaged in small talk, his baggy, melancholy eyes seemed to be on the lookout for thieves.

The saga of the Shubert brothers was now consigned to ancient history — even though its scandalous denouement was quite recent history — and the current monarchs were not about to call attention to it. But I stumbled upon a possible clue to the mystery of how Schoenfeld and Jacobs became “the Shuberts” while researching a book at the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.

Variety had the story, which had not been covered by the major New York dailies because it unfolded during the 1962–63 newspaper strike. Five months after John Shubert’s November 1962 death on that train to Clearwater, a second widow had emerged, claiming to be the matriarch of a second John Shubert family (replete with a new, 2-year-old John Shubert). She filed a suit to challenge the will that had left her husband’s estate to the ex–chorus-girl wife. She revealed that John was en route to a secret home they shared in Florida when discovered dead on that train and that they had also flagrantly maintained a clandestine Shubert household in an apartment directly above the Shuberts’ own 54th Street Theatre. The 54th Street Theatre was literally a block west of John Shubert’s 54th Street home with Widow No. 1. Widow No. 2 claimed that he had obtained a Mexican divorce from Widow No. 1 and then married her. Widow No. 1 claimed that a second will benefiting Widow No. 2 was a forgery.

The battle spilled into Surrogate’s Court. When the dispute was abruptly resolved with an out-of-court settlement at the last moment, Widow No. 1 had triumphed. Widow No. 2 faded into anonymity, as did her two young children, though the settlement allowed the children to retain the Shubert name. It was the previously obscure young Shubert lawyer Gerald Schoenfeld who brokered the deal for Widow No. 1. With her support, his and Jacobs’s ascent to the throne had begun.

When Schoenfeld and Jacobs finally took over the then-fading empire in the 1970s, they vowed to clean up the neighborhood. They refurbished some houses and transferred a hit produced by the nonprofit impresario Joseph Papp, A Chorus Line, from the Public Theater downtown to the Shubert. Nonetheless, when I arrived at the Times in 1980, just five years later, you would hardly notice this ostensible Renaissance. Not for nothing did Rolling Stone declare 42nd Street between Broadway and Eighth Avenue “the sleaziest block in America.” There was a crude justice to that verdict. What were the sleaziest blocks of Times Square, whatever the decade, if not the Boschian apotheosis of the dog-eat-dog culture of greed, thievery, vulgarity, and sexual predation by which Lee and J.J. built the Broadway Theater District from the start?

Much to the latter-day Shuberts’ dismay, the Times welcomed the New Year of 1983 with a front-page article headlined “Broadway Is in Its Worst Slump in a Decade.” The accompanying photo showed a clutch of newly unemployed stage orphans from Annie, the hit musical that had closed that weekend after a run of almost six years. Of Broadway’s 39 theaters, 15 were dark and 11 more were expected to join them in the coming weeks. The year before, ushering in the atmosphere of impending doom, five playhouses near Times Square were razed to consummate a real-estate deal in which a brutalist Marriott hotel would be built on the sites of the original Broadway productions of the signature 20th-century American dramas Death of a Salesman and Long Day’s Journey Into Night. The architectural vandalism was hideous and heartbreaking to watch, inhumane civic renewal by wrecking ball in the discredited vein of Robert Moses. The gaping wound persists to this day. A chronicler of Times Square’s decline named Josh Alan Friedman would later observe that “ironically, not one peep, scumatorium, or topless bar was razed for the Marriott — just the Morosco and Helen Hayes theaters.” (Neither of those demolished theaters were Shubert properties.)

Some of the surviving houses remained empty for seasons on end in the ’80s, their marquees serving as tombstones for the bombs that had fleetingly awakened them from their slumber. In the accounting of the British drama critic Benedict Nightingale in the mid-’80s, some of the most venerable Broadway houses had sat empty for years over the preceding decade — the Belasco for 409 weeks, the Lyceum 294, the Golden 286. Against this grim backdrop, soon to be darkened further by the spiraling AIDS casualties among theater artists, it felt all the more remarkable when something original and transcendent materialized on those Broadway stages that were lit: Sunday in the Park With George, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, Angels in America. The cognitive dissonance between those theatergoing experiences and the catastrophic health of the theater’s workers, its balance sheet, and its neighborhood was hard to fathom and at times tragic to witness. Decades later, I feel the Broadway of the ’80s could be bracketed by two snatches of dialogue that, for me, still linger. In Ronald Harwood’s The Dresser of 1981, the aging aide to a dying Shakespearean actor-manager clings to a fraying backstage mantra while touring the British provinces during Luftwaffe bombing raids: “Here’s beauty. Here’s spring and summer. Here pain is bearable.” In 1990, an upper-crust Manhattanite in John Guare’s Six Degrees of Separation surveys the widening schisms of his city and observes, “Sometimes there are periods where you see death everywhere.”

As I was leaving the critic’s job in the early 1990s, the New York theater was at what everyone (including me) judged to be its rock bottom. One afternoon, I took my young sons to the intersection of 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue. I wanted them to witness an inflection point in New York history. We paused to look west toward Eighth Avenue, surveying the block that once had “a cast of characters out of Dostoevsky, Algren, Spillane, and Gide.” Now, it was a ghost town, unlit and sepia-hued, frozen in time.

I had shown them neon-flooded vintage photos of what 42nd Street used to look like. I explained that the deserted, boarded-up buildings stretching before them were former vaudeville houses and grind movie theaters, peep shows, and greasy spoons, all condemned for redevelopment. Change was on its way. It would soon be announced that Disney had secured a deal with the city and state to restore the best known of 42nd Street’s relics as an active theater: the long-dormant and crumbling New Amsterdam, which dated back to 1903, when the adjacent intersection was still known as Longacre Square.

Sure enough, Disney came to Times Square, and change came with it. Then again, each generation’s Times Square is different from the next, though all are some amalgam of the tawdry and the brilliant, of decay and glitter. What has survived — despite the vanished movie palaces, despite the lame civic effort to impose a mall on its grid, despite every showbiz upheaval from silent films to streaming — are some three-dozen playhouses that keep hanging on even through the dark years out of an impresario’s dream that lightning can still strike onstage. Along with London’s West End, Times Square is the only large chunk of central urban real estate in the English-speaking world that paradoxically survives both because of and despite its dense population of ostensibly obsolete shrines to what is now redundantly called “live theater.”

It was a former Times drama critic, George S. Kaufman, and his playwriting partner, Moss Hart, who first coined the term the fabulous invalid to describe the New York theater in their play of that title — in 1938. It’s kind of fabulous that while everything has changed since then, Broadway, its perennial obituaries included, still remains more in character than much of what surrounds it in present-day New York, New York.

More From the New York Stage

Latest News

For Sale! 2016 Sea Ray 350 Sundancer – $180,000

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

Exclusive Fine Art Partnerships: Pierre Emmanuel Martin

Lemieux et Cie and Pierre Emmanuel Martin: A Harmonious Collaboration in Fine...

A Comprehensive Guide to the White Isle

Ibiza: The Vibrant Heart of the Balearics in 2024 Ibiza, the sun-kissed...

Roschman Sells Boathouse Marine Center to BlueWater for $16 Million

© Copyright – autocontently.com

Man United seals spectacular comeback to beat Lyon 5-4 and advance to Europa League semifinals

Manchester United’s season isn’t done yet. On a night of high drama...

Leave a comment