In the 2002 Neil Young biography Shakey, Young’s late friend and longtime producer David Briggs shared an insight into the singer’s prolific mid-’70s period that has since been enshrined in the halls of Neil lore. “He’d turn to me and go, ‘Guess I’ll turn on the tap’ — and then out came ‘Powderfinger,’ ‘Pocahontas,’ ‘Out of the Blue,’ and ‘Ride My Llama,’” Briggs said. “I’m not talkin’ about sittin’ down with a pen and paper, I’m talkin’ about pickin’ up a guitar, lookin’ me in the face, and in 20 minutes — ‘Pocahontas.’”

Like all good rock-and-roll mythmaking, Briggs’s version of events doesn’t entirely hold up to scrutiny; Shakey clarifies elsewhere that Young started toying with “Powderfinger” in the late ’60s, and it wouldn’t exactly come as a shock to learn that the free-associative final verse on “Pocahontas” about the Astrodome and Marlon Brando was written in a drug-adjacent fit of inspiration. Still, Briggs’s overall point stands. In the span of a few short years, so many songs poured out of Young that it’s taken him decades to release them all.

Since 2017, as an offshoot of the Neil Young Archives, Young has debuted a steady stream of so-called “lost” albums — completed records that he intended to drop when he made them but ultimately decided to shelve for one reason or another. (The most recent one, Oceanside Countryside, came out this month.) Predictably, most of these stem from that hyperproductive stretch of the ’70s, when the singer amassed so much material that he found himself cutting albums left and right, trying to find the best home for each song. In most cases, he succeeded, so the lost albums are full of alternate takes on songs that ended up elsewhere, in addition to the occasional unreleased gem or abandoned curio. While that means the lost records don’t contain too many songs Neil-heads haven’t already heard in one form or another, they do provide a window into how Young chiseled a defining era of his career out of a massive slab of raw music.

“What if” scenarios and alternate timelines abound on these projects, but how do they work as actual albums? I’ve tried to assess that below, but first, some ground rules: I’ve included only the projects that were conceived as studio albums, completed, and then shelved. This means no Early Daze — the compilation that Young recently put out of his early-career studio sessions with Crazy Horse. (Though that’s worth a listen.) And Young has to have put the record out as a stand-alone release, so no albums like 1982’s Island in the Sun or 1987’s Summer Songs, which are only available, for now, in a recent $240 Neil Young Archives box set. Feel free to send me one, Neil.

5. Toast (recorded in 2001, released in 2022)

For a guy whose catalogue has plenty of earnest, devastatingly romantic tunes, Young can still be cagey about what parts of himself he chooses to put out there — a quality that might explain why there are two records on this list that he initially buried because he felt they were too sad. The first is Toast, a collection he recorded with Crazy Horse shortly before scrapping it in favor of 2002’s Are You Passionate?, an R&B genre experiment on which he swapped out the Horse for ’60s soul legends Booker T. & the M.G.’s. Four of the seven songs on Toast wound up on Are You Passionate?, but it’s shocking how little of their usual fast-and-loose, dive-bar-band energy the Crazy Horse boys manage to inject into those songs, often sounding instead like they’re doing an (impressive!) impression of an M.G.’s-era R&B band. The breakup ballads are just idiosyncratic enough to remain uniquely Neil, but the album peaks with the more traditional Horse rockers, like the ten-minute, surf-rock-tinged “Gateway of Love.” If the intermittently successful genre-experimenting of Are You Passionate? gives that album a unique hook, Toast is a replacement-level entry into the latter-day Crazy Horse canon.

4. Oceanside Countryside (recorded in 1977, released in 2025)

By 1978, casual fans who threw on Harvest at dinner parties had likely all but given up on Young ever returning to the radio-ready folk sound of “Heart of Gold.” But after his detour into downer classics like Tonight’s the Night, Young was ready to throw those folks some red meat. The result was Comes a Time, an upbeat country-folk record that quickly outsold all six albums since Harvest. Oceanside Countryside comes from that same vein (even sharing a few songs with Comes a Time) and has a compelling formal conceit: The first five tracks were recorded solo in Florida and Malibu and thus comprise the “Oceanside” half, while Young recorded the more hoedown-friendly “Countryside” songs on the B-side with a full band in Nashville. It’s a fun format, and when the fiddle kicks in on “Field of Opportunity” at the start of the B-side, it gives the album a necessary jolt of energy. That said, there’s not much that’s new here, and while I’ve tried to judge the albums on this list in a vacuum, it’s hard not to think while listening to Oceanside Countryside that Young made the right choice putting out Comes a Time instead.

3. Hitchhiker (recorded in 1976, released in 2017)

At the risk of mistaking mysticism for scientific truth, I think it’s safe to say Neil Young is connected to the moon. Between 1975 and 1977, he spent many a full moon holed up in a studio with Briggs at Indigo Ranch in Malibu, attempting to record songs at the same breakneck speed he was writing them. On one such night in August 1976, Young recorded ten in a row under the simplest of conditions — just himself, a guitar, a harmonica, and the occasional break for weed, beer, or coke. The final product was Hitchhiker, an unvarnished little collection of some of Young’s best songs, made all the more intimate by the occasional missed chord or offhanded moments like the giggle at the beginning of “Hawaii.” You could argue that Hitchhiker is more of a performance than an album, but its stripped-down simplicity is also the ultimate stress test for the songs, recasting “Powderfinger,” for instance, as an undeniable folk standard. My only gripe is that it may have technically been recorded under a waning gibbous.

2. Chrome Dreams (recorded 1974–77, released in 2023)

When Neil played the then-unreleased Chrome Dreams for Carole King in 1977, she laughed at him, saying it was hardly a proper album, and that Young played solo on too many songs. Listening to it now, you can see what she meant. At times, the album is as stripped-down and rough around the edges as Hitchhiker — on the self-recorded “Will to Love,” for example, you can even hear a fireplace crackling in the background. Young opted not to release the album, and most of its songs wound up in other forms on other projects. But Chrome Dreams also took on a life of its own, circulating widely as a bootleg for decades before eventually getting a proper release in 2023. (In 2007, Young called a totally unrelated album Chrome Dreams II — meaning the sequel technically got released first.) Despite the semantics of King’s critique, Chrome Dreams carries a strange power that makes it more coherent in retrospect. Many of the songs here wound up as the centerpieces of the albums they eventually landed on (e.g., “Like a Hurricane” on American Stars ’N Bars), so listening to Chrome Dreams feels a bit like bearing witness to Young’s universe before its Big Bang, seeing all the pieces in one place before they scattered to their eventual homes. It all worked out how it was supposed to in the end. Thanks, Carole.

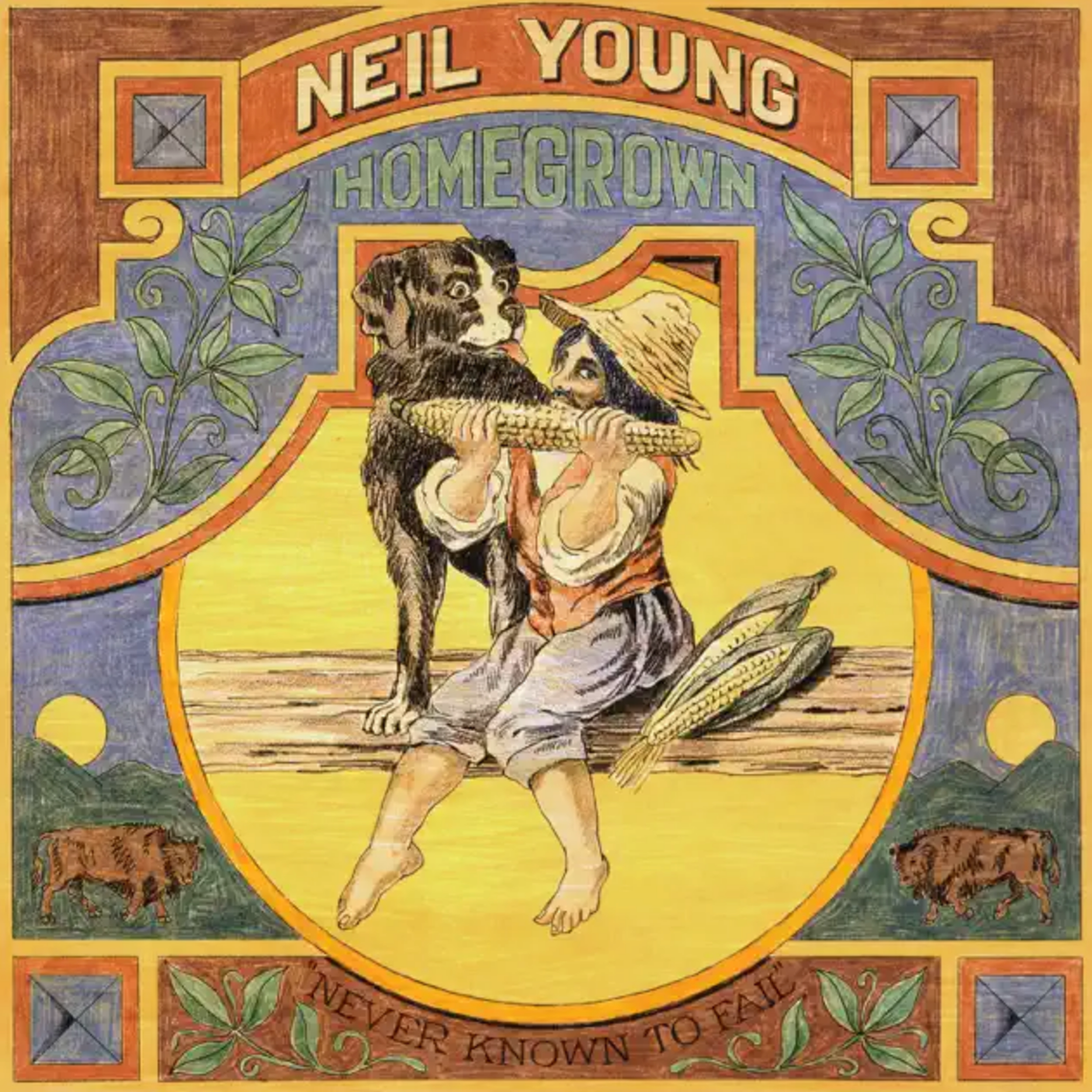

1. Homegrown (recorded 1974–75, released in 2020)

The other record on this list that Young shelved because it felt too raw, Homegrown was intended to be the follow-up to 1974’s On the Beach, until Young decided to put out the dingier Tonight’s the Night instead. When he finally released Homegrown in 2020, Young called it the missing link between Harvest and Comes a Time, presumably because it represents a partial return to the soft-folk sound of his most popular music. But Homegrown is a little stranger than that suggests, chronicling the collapse of Young’s relationship to the actress Carrie Snodgress with uncomfortable specificity. For instance, it’s hard to imagine how anyone could hide away a great song for almost 50 years that features Levon Helm on the drums, until you hear “Separate Ways,” the devastatingly intimate Homegrown opener about co-parenting amid a breakup (“Sharin’ our little boy / Who grew from joy back then”). “Try,” a casually indelible little folk tune with Emmylou Harris singing backup, sounds on its face like any number of lilting, romantic Neil songs from the early ’70s. But it, too, is intimately ensnared in Young’s relationship with Snodgress, with its best line — “I’d like to take a chance / But shit, Mary, I can’t dance” — referring to something her then-recently deceased mother used to say.

The rest of Homegrown plays out like a tour through Young’s different personas at the time, shuffling through rootsy Americana (“Love Is a Rose”) and grungy rockers (“Vacancy”), with a delicate love song or two (“Kansas”) along the way. It probably would’ve satisfied a broader audience than Tonight’s the Night in 1975, but emerging in the throes of 2020, it felt like a small miracle. If Young’s taught us again and again throughout his career that he’ll never give you exactly what you want when you want it, just know he’ll get around to it eventually.

Related

Latest News

For Sale! 2016 Sea Ray 350 Sundancer – $180,000

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

Classic encounter on ice as United States wins women’s hockey worlds 4-3 in OT against Canada

Tessa Janecke scored the winner as the United States prevailed in overtime...

Justin Thomas ends 3-year drought with playoff victory in RBC Heritage

Justin Thomas had one more hurdle to prove his game was back...

Derrick White scores 30, Tatum stays in game after fall and Celtics beat Magic 103-86 in Game 1

As the Celtics were taking control of their playoff opener against the...

Mitchell, Jerome help Cavaliers rout Heat 121-100 in Game 1 of 1st-round series

Donovan Mitchell scored 30 points, Ty Jerome had 16 of his 28...