What you need to know to sail across the Pacific

Coffee in hand, I gaze out from our cockpit across the flat lagoon of the palm-fringed coral atoll in Fakarava.…

Contrasting passages when sailing the Pacific to Hawaii and back revealed the importance of crew dynamics to Tor Johnson

After two recent deliveries sailing the Pacific to Hawaii and back, on two very different boats, with two very different crews, I’m starting to realise that, more than anything else, it’s really the crew that makes the voyage.

Crossing the Pacific from San Diego to Hawaii is widely considered a bucket list trip. It’s mostly downwind in the trades, it gets warmer by the day, and the goal is well… Hawaii. It’s a paradise, and one that I call home. I had the great fortune to skipper a fine sailing boat that I knew well: a 2017 Jeanneau Yacht 53 named Kaimana.

Best of all, my crew were what I would call the ‘Dream Team’: my two nephews, both 24 years old, who – after a number of ocean crossings with me – are capable offshore sailors. Rounding out the crew was retired Navy ordnance chief Tracy Dixon, an old surfing and sailing friend who has also done numerous crossings with me.

The dominant weather feature of the California coast is north-westerly winds. In summer, the Pacific High lies offshore, spinning out strong north-westerlies where it squeezes against the West Coast. The tradewinds that would propel us to Hawaii are also a product of this high pressure zone. San Diego owes its balmy climate to Point Conception to the north-west, which protects the city from most of these winds.

Kaimana hooked into the north-westerly tradewinds on passage from San Diego to Hawaii. Photo: Tor Johnson

Though reluctant to use fuel so early in the trip, we resigned ourselves to motoring out initially to meet the north-westerlies. It wasn’t until about 100 miles offshore that we began to feel their effect, but once they filled in, we were in for a fast, close reach. The boat came alive, popping, groaning , and creaking as we corkscrewed through moderate breaking seas in 20 knots of wind.

Of course there were issues: Tracy came down with Covid, just as we started taking water over the rail in the building seas. When the tanks got stirred up, we discovered that our water was tainted, the taps spitting out a nasty, milky sludge.

As if this weren’t enough, we found oil rising in the bilge. This turned out to be from the generator, which happened to be nearly inaccessible at sea, via an aft hatch a few inches above the waterline. Further along in the Pacific Gyre, debris wrapped around our prop, pieces of vast abandoned ‘ghost’ fishing nets.

Pacific expanse… and a rare black-footed albatross for company. Photo: Tor Johnson

Yet we managed to overcome the challenges as a team. When Tracy fell ill I was able to take his watch, because both my nephews could handle the boat while I got some rest. We solved our generator issue by taking off the transom cover on a calm day as we slid along at nearly the same pace as the following seas.

We found a large supply of distilled water bottles from our last crossing to the US mainland, appropriately labelled ‘Aloha Water’. And Quinn, a keen surfer, simply had to be the guy who dove down and removed fishing nets from our prop.

After the north-westerlies faded, they were replaced by the north-east tradewinds. Temperatures rose by the day, and we happily shed our heavy jackets. Coastal fog slowly gave way to the small puffy cumulus clouds characteristic of the dry winds descending out of the high pressure area.

We set a new Doyle asymmetric spinnaker – bright pink and quickly dubbed Margot, after Margot Robbie, crew favourite and star of the Barbie movie. Kaimana surfed downwind, pushed by a rolling, impossibly purple sea.

Cockpit mealtimes with the whole crew. Photo: Tor Johnson

We doused Margot at sunset and put up the 130% genoa, so as to avoid wrapping the spinnaker at night. This was after all a delivery, and the goal was to deliver the sails in one piece, as well as the boat and its crew.

Yet conditions were so favourable we arrived off the wild north coast of Molokai, ahead of schedule after only 14 days, and still with two-thirds of our fuel remaining in the small 238lt (63gal) tank.

We still had to cross the channel to Oahu, but with the owner’s permission we stopped for a day and swam with spinner dolphins to celebrate a safe, if not entirely trouble-free, crossing. I admit that being both uncle and captain at the same time could be difficult, especially when some in the crew wanted to leave all sail up during a squally night, but in general we got along well.

The return voyage to the US West Coast was, by definition, a bit more work. The first part of this crossing involves fighting up into the tradewinds to penetrate the Pacific High pressure area, to reach higher latitudes where winds are generally west, or variable.

Famously turquoise clear waters for Kaimana off Waikiki, Honolulu. Photo: Tor Johnson

I wasn’t initially ready to put out to sea again, but I’d been asked to make this trip to Anacortes, Washington, by Craig Gifford, a good friend and an airline pilot on Vivace, his beautiful 2018 Amel 55. The Amel is arguably the perfect boat for a passage to windward like this: a heavy, good sailing Berret-Racoupeau ketch with a well-protected cockpit enclosed by a hard dodger.

Gifford was captain, and I was crew for a change, fulfilling the experienced sailor role now required by insurance. Craig also enlisted his own nephew, 17-year-old Miles, and his brother Mike as crew. Craig had just done his first ocean crossing to Hawaii with an instructor, getting his offshore certification in the process.

The Amel showed her heels early, rolling quickly downwind in the tradewinds between Oahu and the emerald isle of Kauai. At dusk we entered Hanalei Bay, surrounded by high, nearly vertical crenelated mountains covered in riotous green. Outer reefs protect a two mile long, fine, white sand beach, where the sandy bottom descends to perfect anchorage depths.

Hanalei is paradise in summer, one of the island’s most spectacular anchorages. When winter swells arrive the bay becomes untenable, and transforms into a different kind of heaven; a world-class surf spot with a perfect right hand point.

Keen surfer Quinn dove beneath Kaimana to clear a fishing net prop wrap. Photo: Tor Johnson

But the crew was itching to start the crossing. It’s something I’ve seen before: everyone gets keyed up to start a big trip and loses interest in exploring a magical place they may never see again. I told Craig that since he’d sailed across an ocean to get to Kauai, one of the most beautiful islands on earth, he might want to soak it in.

We stayed. Craig had a blast wing-foiling in the gin-clear water, until his wing shredded and I had to rescue him in the dinghy. He let me have a go, and I managed to get up on the foil after a lot of work for about 10 seconds.

As we sailed away from lush Hanalei Bay, bound for Anacortes, Washington, I played ‘Hele on to Kauai’ by Hawaii’s most beloved musician, Israel Kamakawiwo’ole, on the stereo. We accelerated away as the water descended from sparkling bright blue to the deep indigo purple of the open sea. It was so beautiful I actually teared up, pretending I caught some spray in my eye.

Vivace muscled her way up against the tradewinds for four days, heading mostly north. Unfortunately, as we beat our way into headwinds and seas, a diesel leak developed in the fuel tank, right under my bunk. Diesel began flowing out onto my cabin sole and the fumes became almost unbearable. Mike and I chased the leak for days. I eventually dismantled my bunk, found the leak coming from an inspection port under my pillow, and put a stop to it.

Article continues below…

Coffee in hand, I gaze out from our cockpit across the flat lagoon of the palm-fringed coral atoll in Fakarava.…

We leave Tahiti with strong trades. Easterlies funnel along the side of the volcanic island, and Elixir tears downwind toward…

On the passage I started reading The Ship Beneath the Ice, the fascinating tale of the painstaking discovery of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s vessel Endurance under the polar ice pack, written by expedition leader Mensun Bound.

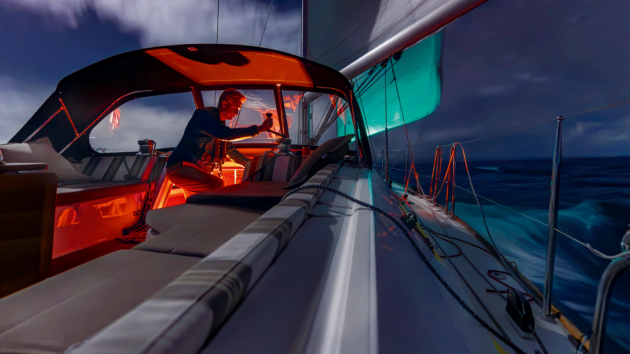

A relaxing evening on a Pacific crossing aboard the Amel 55 Vivace. Photo: Tor Johnson

Self-confessed Shackleton fanatic Bound uncovered unpublished accounts and diaries of the Endurance crew in his research. Reading his account, I began to realise that the very survival of Shackleton’s 28 men after a year on the ice depended not just on their famous leader, but on individual crew members.

Yes, there was friction between them. People being people, no voyage is without disagreements, especially one with such horrific privation and hardships. Though Shackleton never mentioned the extent to which his men were constantly annoyed by each others’ habits and characters, Bound learned that the mechanic, Major Thomas Orde-Lees, snored so terribly that his crew mates tied a line around his arm so anyone could wake him, and when that didn’t work, banished him to a shed.

There were fist fights, theft of provisions, and rebellion. Even Mensun Bound, with his highly professional team searching under 300m of water and pack ice for the elusive wreck of the Endurance, said the mission was sometimes ‘more about managing egos than archaeology’.

When the Endurance was crushed in the ice, and Shackleton’s crew forced to abandon the vessel for an ice floe, a large amount of their provisions remained aboard the slowly sinking ship. Shackleton forbade them to try to retrieve the stores below decks as the ship began to sink, and the critical supplies were trapped, inaccessible under several feet of ice and water.

Memorable days of sunshine and a steady Pacific breeze. Photo: Tor Johnson

It was – fittingly – the photographer who saved the day. Australian Frank Hurley came up with a way to free the stores. Using a very sharp ice chisel attached to the end of a spar, and wielded like a pile driver, they bored holes into the massively reinforced deck of the Endurance, fishing out about two tons of food. Without those supplies it’s doubtful they’d have survived as they did over a year in harsh Antarctic conditions.

Not to discount Shackleton’s leadership, and bravery, but without men like Hurley, or the incredible feats of navigation of New Zealander Frank Worsley, or the superb small-boat sailing skills of sailor Tom Crean, they’d likely all have perished.

Voyages like the Endurance are extreme examples, but even on a ‘routine’ ocean crossing like ours, crew dynamics were crucial. Captain Craig, for example, is an airline pilot, meticulous to the point of obsession. As we beat up around the high, Craig would clean the entire deck, stem to stern daily.

Tor Johnson and an impressive hand-line catch aboard Kaimana. Photo: Tor Johnson

He’d then continue below, bleaching and scrubbing everything in sight. This was a bit disconcerting to the crew trying to relax off-watch, who were predictably annoyed. I reasoned that there are worse traits in an airline captain than obsession with detail. The hundreds of passengers he is responsible for on a daily basis might appreciate his thoroughness.

All the same, Craig was under pressure as captain, and he and his brother could get on each other’s nerves sometimes, as brothers do. Trying to de-escalate, I pointed out that this was a voyage they’d probably remember for the rest of their lives. How they remembered it was really up to how they handled things. Sure enough, the brothers now reminisce fondly about the Pacific crossing.

As a pilot, it also followed that Craig had some serious VHF skills. When our AIS showed a vessel approaching on a converging course, Craig didn’t waste a minute, calling in a clear radio voice using the DSC function: “Container vessel XXX, this is sailing vessel Vivace, under sail. Closest point of approach is 0.2 miles. We will pass astern of you, starboard to starboard.”

He repeated his transmission, and the crew responded right away. According to Craig, a DSC call gets more attention because it must be recorded in the ship’s log – something he well understands in commercial aviation where logs are often scrutinised.

Majestic backdrop as Vivace sails out of Hanalei Bay on the ‘garden island’ of Kauai, Hawaii’s fourth largest island. Photo: Tor Johnson

Unlike the tradewind passage to Hawaii, variable winds are the norm for the North Pacific, where the gradient from the Pacific High is less pronounced, and passing systems have a bigger effect. Our PredictWind software was useful, but we didn’t take the routing advice as gospel, instead using it as one piece of input. We found that shaping our own course through the systems set us up for the best winds as they changed north of the high pressure.

Amel was one of the last production yards to build a ketch (now it’s sloops only), a rig that allows for smaller, more easily-handled sails by balancing the sail plan across more sails. In a real blow we even had the option to sail comfortably under just the staysail and mizzen.

The steering console carried all sail controls, each sail furling via its own electric furler. Graphic displays showed icons of sails and furling gear. Craig remarked that he liked the setup because “it’s almost like flying an Airbus”.

Setting up Vivace’s Code 0. Photo: Tor Johnson

This was where Miles, his 17-year-old nephew, really shone. He understood the idiosyncrasies of each instrument, a big help for the rest of us. Having cruised with Craig in the Pacific Northwest, Miles already had a good grasp of sail handling on the boat.

When the wind picked up we rolled up the big genoa and set a nice flat blade-shaped staysail (on its own automatic furler), which made the boat a joy to sail upwind in a breeze. Once above the high, we used the powerful Code 0 to keep the boat moving well in the relatively light upper latitude variables and westerlies, across to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Vivace had company in the form of a black-footed albatross, a rare bird that mates for life only in the North-western Hawaiian Islands, and ranges all across the Pacific in any weather with seeming ease. We landed plenty of fish, thanks to some sturdy 300lb hand lines I’d brought. But our albatross friend refused to accept any of the fish pieces I threw for him, perhaps preferring to catch his own, and remain unbeholden to us.

Being from the Northwest, both Miles and his father Mike were adept at fishing, and took to the idea of hand-lining like naturals, pulling in albacore tuna at an impressive rate. Once a fish was hauled in and brought on deck thrashing, they’d leap on the fish, pinning and immobilising it as only someone who really knows his way around a fish can do.

Tor Johnson and his wife Kyoko run their photography business out of a beach house in Waialua, Hawaii. Tor, a lifelong surfer who grew up sailing the oceans with his family, now sails his own Jeanneau 44i Keala and delivers yachts for others. Photo: Tor Johnson

We rarely lost one. We ate the tuna raw most of the time, often making Hawaiian ‘poke’, marinating the fish in sesame and olive oil, onions, and salt, and serving it over hot rice, and Craig made some amazing ceviche, marinating the tuna in lime. If a well fed crew is a happy crew, we were happy.

We carried a favourable wind almost as far as the Strait of Juan de Fuca, but it sadly died about 50 miles from shore. Night fell as we approached the strait under power, and a number of brilliantly-lit fishing boats kept us busy trying to stay out of their way.

We considered stopping at the historic Makah Indian village at Neah Bay, just at the entrance to the straits, but the crew voted for a night in their own beds, so we carried on for Anacortes, riding a strong flood tide all the way to the boat’s berth in Cap Sante Marina.

Moonlit night watch during a Pacific crossing. Photo: Tor Johnson

Problems on any boat are a given. Once a boat goes offshore, things just seem to break or fail. And there will be friction. With stress, lack of sleep, constant motion, and varied characters, we will get on each others’ nerves. How the skipper and crew handle those issues, managing the strengths of each person aboard, can make the difference between a safe and enjoyable passage and a disaster. Really, it’s all about the crew.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

The post Sailing the Pacific: ‘As we sailed away from lush Hanalei Bay, it was so beautiful I actually teared up’ appeared first on Yachting World.

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

Mach Conferences & Events Ltd. Partners with Cordelia Cruises: A New Era...

Mikko Rantanen has gone four games in a row without scoring, which...

Scottie Scheffler and John Pak enjoyed the same start to the Charles...

Caitlin Clark says it’s a great time to be a basketball fan...

Leave a comment