When Salome calls for Jochanaan’s head, the Metropolitan Opera can really give it to her. In Richard Strauss’s opera Salome, an adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s play retelling the biblical gospel, Princess Salome falls in love with Jochanaan — probably better known to American Bible-quizzers as John the Baptist — and then demands his severed head from her lecherous stepfather, King Herod. After she gets it, she holds it up and kisses it. It’s the climax of the story, accompanied by what’s been described by the scholar Gary Schmidgall as “the most sickening chord in all opera.”

Creating a prop head that looks exactly like baritone Peter Mattei, who’s singing the role starting on April 29, fell primarily to the wigs and makeup department at the Met — a ten-person team headed by Tera Willis. “A lot of people outsource most of their stuff,” properties master Jason Hamilton says. “We’re lucky to have a department dedicated to making props, a department for wigs and makeup, wardrobe, a costume shop. There aren’t many theaters that can do that.” Still, in Willis’s words, ten people is an “exponentially small” team for the amount of work they have to do, because the Met is a huge performing-arts factory, with new productions, shows in repertory, and singers constantly coming and going. On the day we chat, she is thinking about Salome, the filming of Le Nozze di Figaro, an incoming cast for Aida, and the upcoming productions of Antony & Cleopatra and Queen of Spades. Plus, in the back of her mind, there are the cast changes for Madame Butterfly next season, for which she’ll need a slew of new wigs. Nowadays, it all has to be HD-ready since Met productions are shot and broadcast to movie theaters on screens where every silicone pore is the size of a dime. As Willis speaks about all the demands on her department, she occasionally evokes Emily in The Devil Wears Prada, murmuring the reminder, “I love my job, I love my job, I love my job.”

This particular job, though, is unusual. The production is coming in from Russia, where it had its first run under Claus Guth, who is also directing here, so the Met’s designers knew what they were getting into — and it’s an uncommon aesthetic for many of them, stark and a little creepy and therefore a little more exciting.

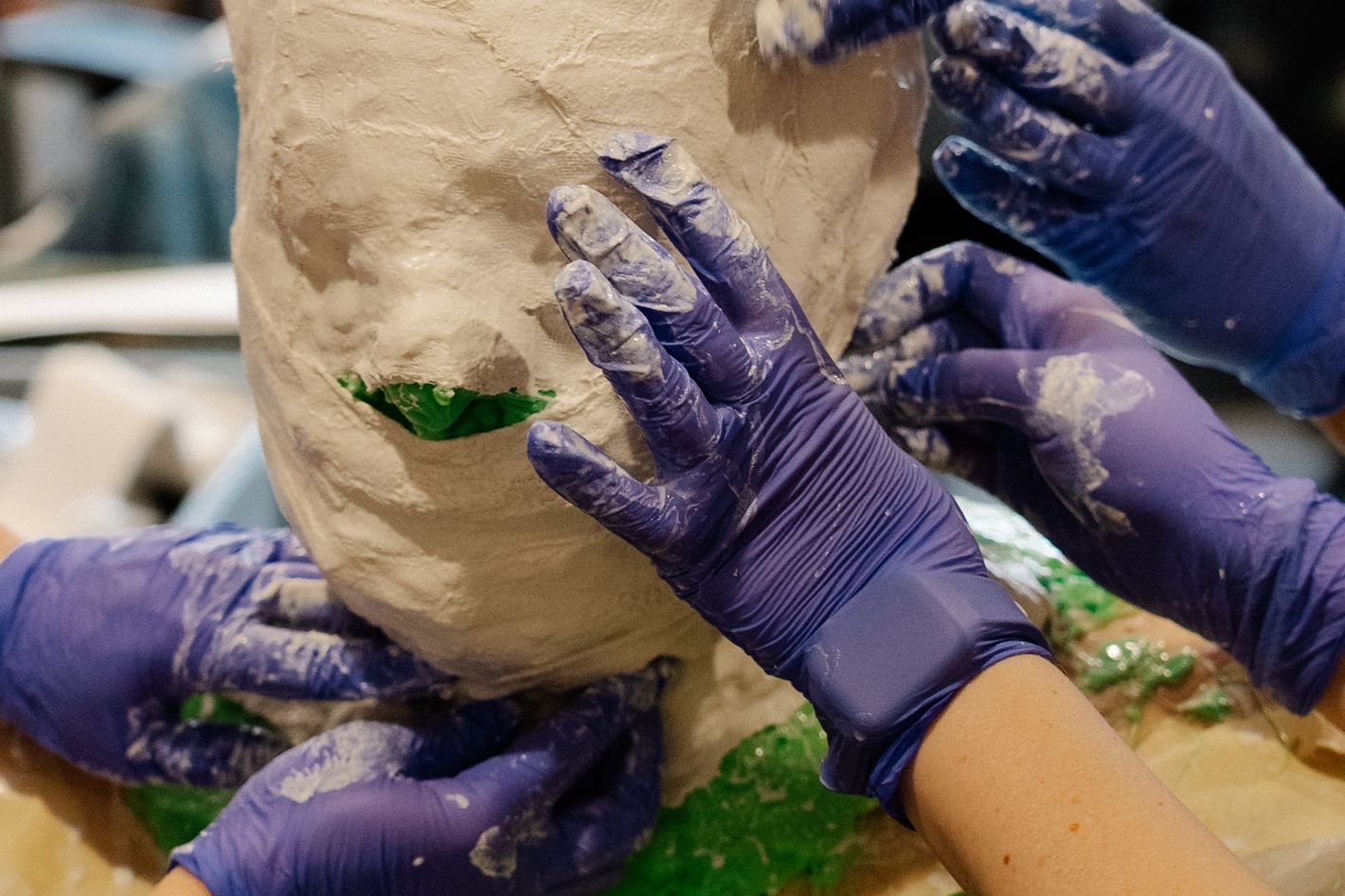

First off, they have to cast a mold on Mattei himself, and, Willis says, they start by taking steps so Mattei won’t get stuck inside. “We put him in a bald cap and put Vaseline through any facial hair, eyebrows, and lashes so we didn’t accidentally snag one” when the casting comes off. Then the pour begins: “That green goop you see is called Body Double, and it’s a skin-safe silicone. You really want to be prepped because you want to be calm as well in the process. We have a person on the back and two people really on the front. I always have somebody on nose patrol, because everything’s going to start running down until it sets up. So you want to have one person there to make sure that the nostril is completely clear at all times. They used to put straws in people’s noses. I don’t do that, because it distorts the shape of the nostril.”

Mattei had a cold the week before and was a little nervous about getting layered up in goo, “but it was no problem,” he says. “You just sit there and keep put in a very meditative way. I think my pulse went down really low.” Plaster bandages, the type used in bone-setting casts, go over the glop. Mattei describes the feeling as “like a really heavy helmet.” That crust holds everything in place: “If you don’t have a stable shell, it’s not going to stay in its shape,” Willis says. And then “you will feel the plaster start curing,” at which point it gets hot. “We like to say that people get a steam facial treatment under there. Then it cools down, and that’s when you’re good to go.”

Then they have to get it off him. “We typically ask them to hold their hands in their face and start making funny faces so that silicone starts releasing,” Willis explains. “We ended up using a casting silicone that doesn’t stick to hair. It takes a minute to pop off, because we’ve got ears in there, it’s pretty tight, so we get people to move around. We get our hands in there and we release it and then he’s done.” Mattei, who grew up a bit claustrophobic, fortunately no longer has that issue. “I had a summer job when I was 18 working in a very bad place,” he says. “We cleaned up industrial tanks, and sometimes I also got stuck. I knew I had a lot of claustrophobia, but there was no other way to do it. So I think I got rid of the panic that summer.”

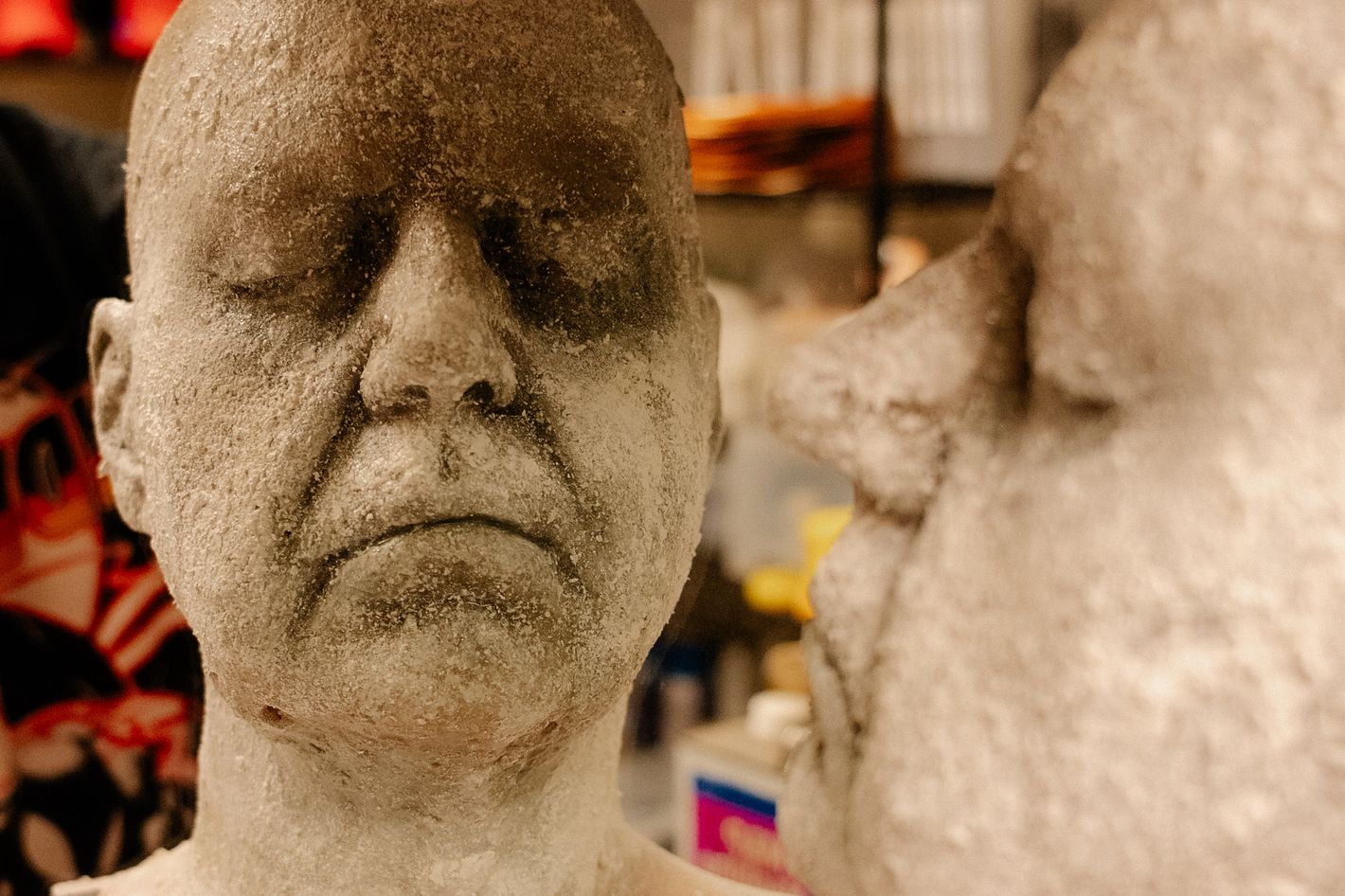

After the mold is finished, the makeup team pours in skin-colored silicone, building up four layers — which, on this occasion, turns out to be a mistake. “We didn’t realize that within the world of the show, a child has to hold this head above their head for a significant amount of time,” Willis says. “I probably should have dug a little bit and found that out. But we sent the almost finished product to stage, and it turned out it was a lot heavier than the rehearsal head they had been working with.” They try making alterations to it, but it still wasn’t the weight it needed to be. That’s when Willis realizes that they needed an entirely new head. “Shit happens and it’s live,” Willis explains. “We have to be very, very flexible here.”

To fix the issue, Willis calls on Susie Knowles, a member of her team who, she knows, has the skills to cast the new and lighter head, using the same mold, in a single day. This time, they use only two layers of silicone, and inside is “an expanding foam — foam urethane — that’s very lightweight.”

Then they ask the scenic team to help paint the head, since that team has already worked on Jochanaan’s remaining half — that is, the dummy that stands in for his dead body. Willis says they got a little lucky with the paint job, because the gory nature of the assignment means the faux skin could look a little rougher than usual. “Oftentimes you take a cast off the singer and you pour a plaster positive to catch any air bubbles,” she says. “Then you go on that one and you chisel those pieces away, and then you take another cast of that. Then it’s perfect. There were a few imperfections and air bubbles here, but, because there was a textured paint treatment, I knew that it wouldn’t get in our way. So we skipped that step. We were able to save a little time and money.”

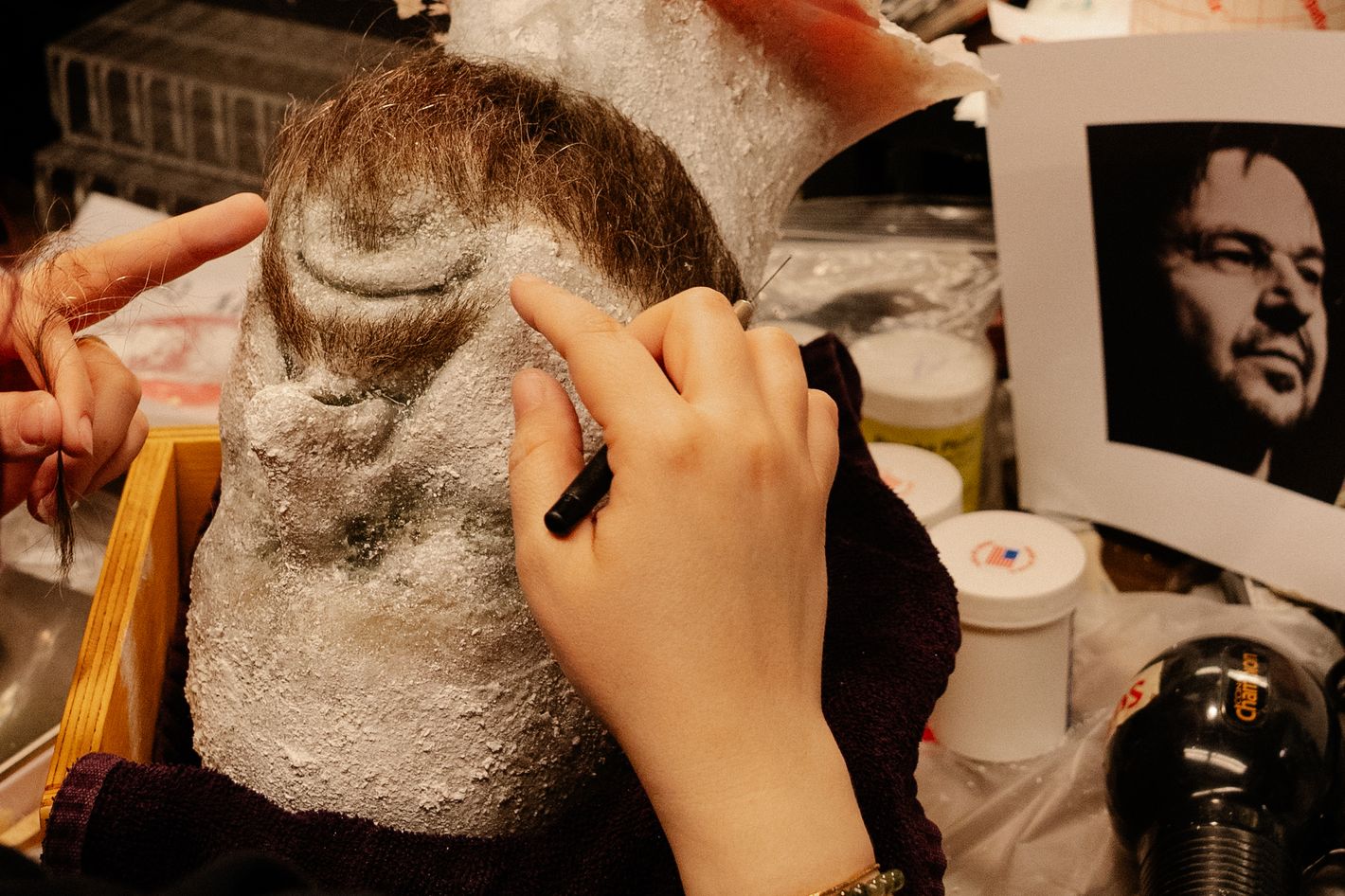

Finally, it’s time for finishing touches. Typically, all the hair on a project like this is inserted into the silicone one strand at a time, a process the craftspeople call “punching hair.” To save time, especially on the head that had to be remade in a rush, Willis figured out some workarounds. “We found a wig that works,” she says. “And we found an already built beard that would normally go on a person and a mustache. Plus, we made some eyebrows.” From there, they finish by punching: “We’re filling in spots and we’re going to go around and do the front hairline,” Willis says. “So instead of doing the full thing, we’re getting 90 percent there with existing hair, then we’re going to finish the last 10 percent with film-quality punching.” Looking over the job, Willis seems weary but proud. “No one in their right mind would ever do this,” she says. “We turned that one out really quickly, but that’s just our education” — both Willis and Knowles went to the University of North Carolina School of the Arts — “and knowing products.” She adds that “a lot of times people call us a glam squad, which I absolutely abhor. Our skill set goes so far beyond making people pretty.”

All photographs courtesy of Muriel Steinke/Met Opera.

Related

Latest News

For Sale! 2016 Sea Ray 350 Sundancer – $180,000

Reel Deal Yacht is pleased to feature a meticulously maintained 2016 Sea...

World ranking chair Trevor Immelman says LIV has not reapplied and ‘the ball is in their court’

LIV Golf getting world ranking points would start with the Saudi-funded league...

MLB offense rises with temperature, batting average of .242 up from .240 through April last year

Baseball offense has picked up as the temperature has climbed in much...

Warriors return home to Chase Center with another chance to close out 1st-round series with Rockets

With his team trailing by 27 points to the red-hot Houston Rockets...

Scottie Scheffler returns to hometown Byron Nelson, takes 1st-round lead with 10-under 61

Scottie Scheffler is happy to be back at his hometown event and...

Leave a comment